Exile and Return – A group exhibition commemorating the 80th anniversary of the liberation of the Bailiwick of Guernsey from Nazi occupation. Part 2.

As part of the Exile and Return Exhibition this May, as a landscape painter, I wanted to create my contribution around the subject of the German fortifications. These were built by the Nazis during the occupation of the Channel Islands in WWII. In viewing these fortresses and bunkers as sites of memory and history, it felt important to understand how they came into being.

Thousands of labourers carried out the relentless task of building these brutalist concrete constructions that, after 80 years, are now an almost accepted part of our coastline to local people. The majority of islanders today will have grown up with their presence. However, in 1945 and 1946, they must have felt like a strange hostile presence for the thousands of returning evacuees and soldiers, including my maternal grandparents. The landscape must have appeared irredeemably ruptured by these sinister jarring structures.

My Grandmother had told me many anecdotes about her return to Guernsey. She had mentioned that one of the derelict cottages, in Mount Durand where she and my family lived, had been used by some of the slave workers as a shelter. On her return, the whole area carried the odour of rotting fish, as piles of fish bones and waste matter was heaped outside the building: the meagre scraps of food that these starving men had to scavenge and catch to survive on.

To set the occupation in context, following the defeat of France, Winston Churchill decided that British troops be withdrawn from the Channel Islands and redeployed. This left the five islands completely demilitarised. Around 25,000 occupants were evacuated to Britain including almost all of Alderney’s residents. This represented around half the population of Guernsey and a fifth of the people from Jersey. Residents born outside of the islands were deported to internment camps in Biberach, Germany.

Life was very different for local people living under occupation. The currency was changed to the Reichsmark, all news sources like the radio were banned and everyone had to drive on the other side of the road. Cinemas only showed German propaganda films and schools had German books. Anyone who disobeyed orders faced imprisonment or deportation to Nazi prisons, labour camps and concentration camps. By the end of 1944, food shortages were terrible and starvation was only alleviated in December by a Red Cross ship, the Vega, bearing food.

Organisation Todt (OT),which built the fortifications in the Channel Islands, was the civilian building arm of the German Services, headed up by Fritz Todt and Albert Speer. It was initially used to construct a megalomaniac vision of an imperial centre in Germany and a motorway network that scrolled outwards into the occupied territories. After war had broken out, the workforce repaired roads, railways and bridges and worked on the cross-Channel coastal artillery batteries in Calais, the French Atlantic coast and the Channel Islands. Hitler believed the Channel Islands might be a ‘stepping stone’ from which to invade Britain. The Islands’ capture was also viewed as a propaganda tool, to show that the Nazis occupied British land. To achieve this end, 10% of the steel and concrete used in Hitler’s “Atlantic Wall”, and one twelfth of the resources, were used in the Channel Islands.

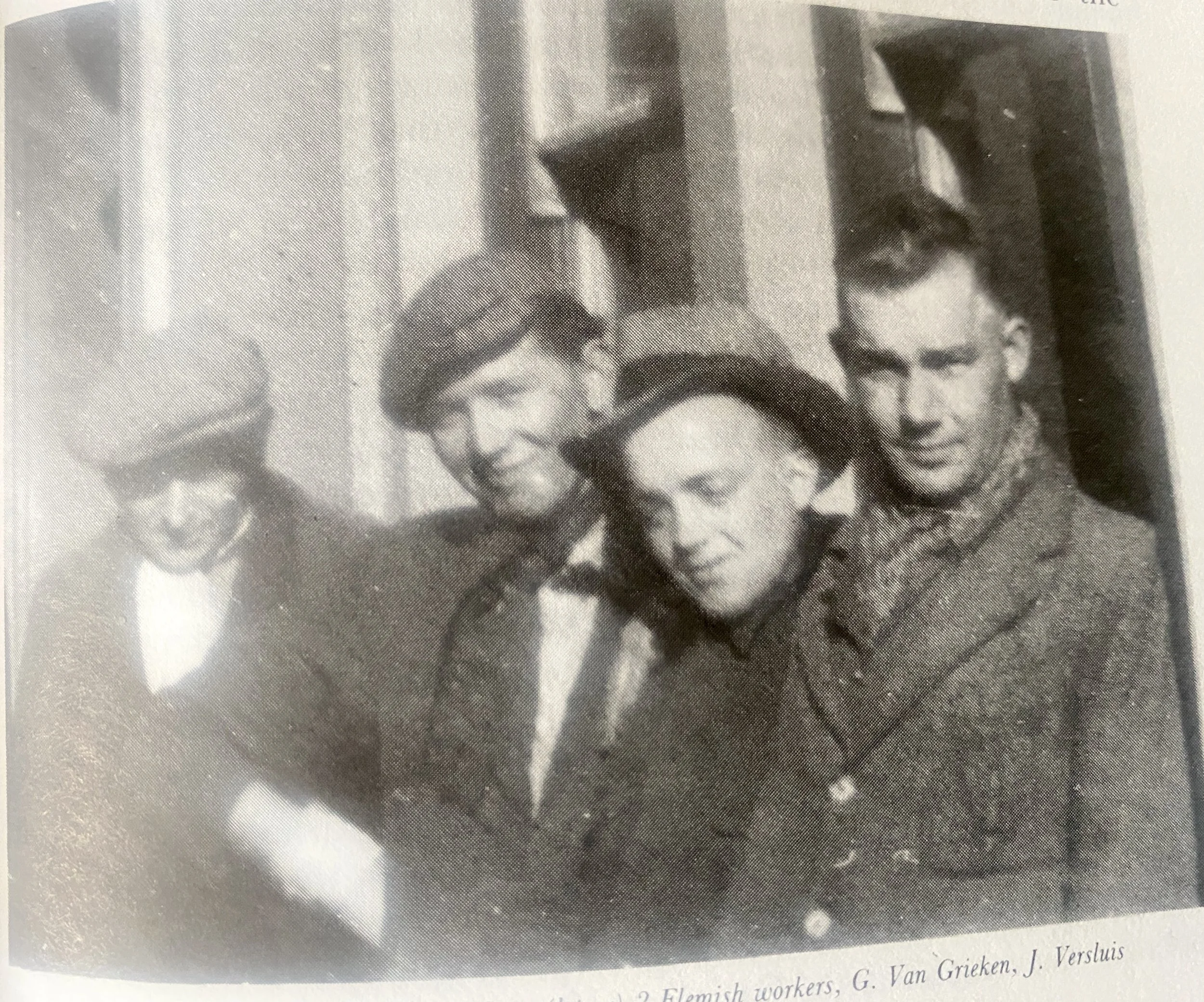

As in the other occupied territories, civilian construction firms and workers were employed from both occupied Europe and the islands. Other unemployed labourers from France, Belgium and the Netherlands were conscripted to work on the buildings. The OT workers wore the khaki uniforms of the German skilled workers (surveyors, blacksmiths, welders, carpenters etc). The unskilled workers who had worked as labourers in Germany and on the motorways became the overseers of the large number of forced labourers which OT gathered from the occupied countries of Europe.

Prisoners of War and inmates from the Neuengamme concentration camp were brought over from Europe as slave labourers to build fortifications and tunnels, along with around one thousand French Jews. Others were indiscriminately rounded up in their countries under a compulsory work scheme, including some school aged boys. Forced Labourers in the Channel Islands were often referred to as “the Russians”, but the greater number consisted of Polish workers, Algerians, French Jewish men and Spanish Republicans. Nazi party members regarded the forced workers as ‘Untermenschen’ (inferior people).

Islanders in Guernsey who took pity on the harsh treatment of these men were severely punished. In Alderney, the Nazis established four concentration camps to hold the prisoners. By 1943 the total number of forced labourers on the island was over 4,000. Conditions were harsh and many of the prisoners were murdered

In a report commissioned by Lord Pickles, President and UK Special Envoy on Post Holocaust Issues, a panel of 13 international experts found evidence that the number of murders in Alderney was likely to range between 641 and 1,027. While a definitive list of names of those who died in Alderney was impossible to achieve, experts said they have created a database gathered from a wealth of archival information, that was often ‘hiding in plain sight’.

The majority of the workers who constructed the fortifications were returned to France in October 1943 where they worked on sites for flying bombs. Many made off into the woods when the Allied Forces landed in Normandy in June 1944, but gave themselves up to American troops and were questioned about the tunnels in the Channel Islands, to find out if these contained secret weapons, but they did not.

***

During my own research, I looked in the Bailiwick Archive to find out more about the labourers. It contained records of all the individuals brought in to do the construction work. Seeing the typed or the curlicued handwritten script of the German administrators outlining the names and addresses of origin of these men (and a few women), it really made the reality of this period more palpable and horrifying.

Letters from the Platzcommandantur were included in the archive files and it was chilling to see these letters, headed with local addresses, signed “Heil Hitler” at the end of the correspondence. Letters from the Controlling Committee of the States of Guernsey, continued with some of the administration work of the Guernsey government. This included granting some identity permits to Todt workers who had married local women.

The German forces began surrendering the Channel Islands on 9 May 1945, as Nazi Germany had been defeated.

Film archives were available on Youtube Channel Islands Part 4 - Organization Todt - Der Westwall - Battery Mirus - Occupied Guernsey showing some of the fortifications being created. The faces of some of these men and boys in the film looked haunted, being marched in large numbers around the islands by armed German soldiers. At points the film focuses on the feet of some of these men. Many of the slave workers’ feet and lower legs are swathed in wrappings that resemble the cement bags, that when full, weigh down their gaunt frames. Often arriving during summer time, they had no clothing or footwear to withstand the bitter winter winds of the islands, so were forced to make improvised protection from whatever could be found.

I started by making some charcoal drawings of the film stills that I had captured on my phone - many of the screenshots taken from the film were out of focus and blurred, which somehow made them feel all the more otherworldly and heartrending. The eyes of a marching labourer stare guardedly out at the cameraman - it is unclear whether this is a silent rebuke or a plea. Others captured the conscripted and paid OT workers with their berets and uniforms pick-axing and shovelling the rugged landscape to lay the steel frames and foundations for the blocky concrete fortifications, often in the hot sun.

After this, I then worked on small wooden panels using the drawings from the reference material. The use of colour in the paintings is non-naturalistic. This is because, for me, painting is more about creating a sense of atmosphere and place through the materiality of paint, rather than a visual likeness. I wanted these to be small intimate paintings that viewers could get close to, unlike the landscape paintings which need distance. I like the idea of the viewers unconsciously choreographing their own steps, forward and back, through the exhibition space as they move between sombre landscape and the ‘intimate immensity’ of the tiny figures.

While making this work, I was thinking about my family, their life before the war in the Island, and the profound sense of loss they must have felt while experiencing occupation, and evacuation. To give a sense of life as it was for them before the occupation, here are a few photographs of them, including my great-gran and her formidable sisters dressed in their best, enjoying life at home and in the local landscape.

The beaches cliffs and common land are important sites of remembrance and of social connection. They allow anyone here to revel in the natural world, as people have done for centuries. To do so is one of life’s great pleasures; one that is still accessible to those of us who are not financially wealthy. It is important that site such as this, and the raft of spaces once used for the horticultural industry, are not exploited by those who see only the financial worth and the development potential of land, or view it as a means of attracting the affluent to the island. This model has been tried and dismally tested by the Barclay Brothers in Sark, at great trauma and heartache to local families, so should be a wake-up call to local people who do not wish to see the Bailiwick become Monaco-by-Sea.

The images of historical Guernsey life are a fertile source of reimagining and interpreting how it was to live in the Islands and how the future might be, at a time before the island revolved around the pro-market policymaking of neoliberalism. With little challenge locally, as everywhere else, this has invidiously become the premise that is seen as the sole legitimate organising principle for human life, with its tiny group of winners, and vast swathe of losers.

The land in the islands is valuable to different groups in different ways. It could easily be exploited if planning policy is liberalised - a direction policy seems to be moving in. Only recently, land in a fairly built up area, where greenhouses have been left to slump and disintegrate in the winter winds, has been given permission for housing. It will be interesting to see if this is used for much needed social housing or for large and profitable private projects. It should be borne in mind that many of our politicians own horticultural land, and while many of them may care deeply about biodiversity and ecological issues, others may have a more short-sighted vision.

The Island is likely to change drastically in the coming decades with the dystopian future that neoliberalism promises, with its acceleration of climate emergency and the exponential loss of biodiversity. Lets ensure that wild spaces still remain and remain for all, and that those who continue to pollute and destroy our world are constantly challenged at both a local and global level.

***

I have a real sense that this body of work will grow and develop long after the exhibition ends. Using archive material has been a revelation: a creative wellspring and a highly emotional and impactful way of learning about the past as a contextual source for painting. It has also made me reconsider using photographs as source material in my painting practice - a process that I had previously found deadening and unintuitive, preferring to draw from life.

As this article was getting rather long, I will break off here. I hope to continue writing about this project in the blog, looking next at why art that focuses on the impact of warfare and displacement is important. I was thinking about this frequently when making this work, while also looking at the many artists and art writers within the wider discourse of painting (and wider fine art practice) who made work dealing with conflict, war and the holocaust.