Mysterious and Dark Guernsey Landscapes

In late March this year, I’m taking part in a joint exhibition with the documentary photographer Aaron Yeandle. My last blog post looked at the reason we wanted to put on a joint landscape exhibition and focused on the similarities and differences both in our work, and in painting and photography generally. In this article, I really wanted to focus on Aaron’s landscape photography in its own right.

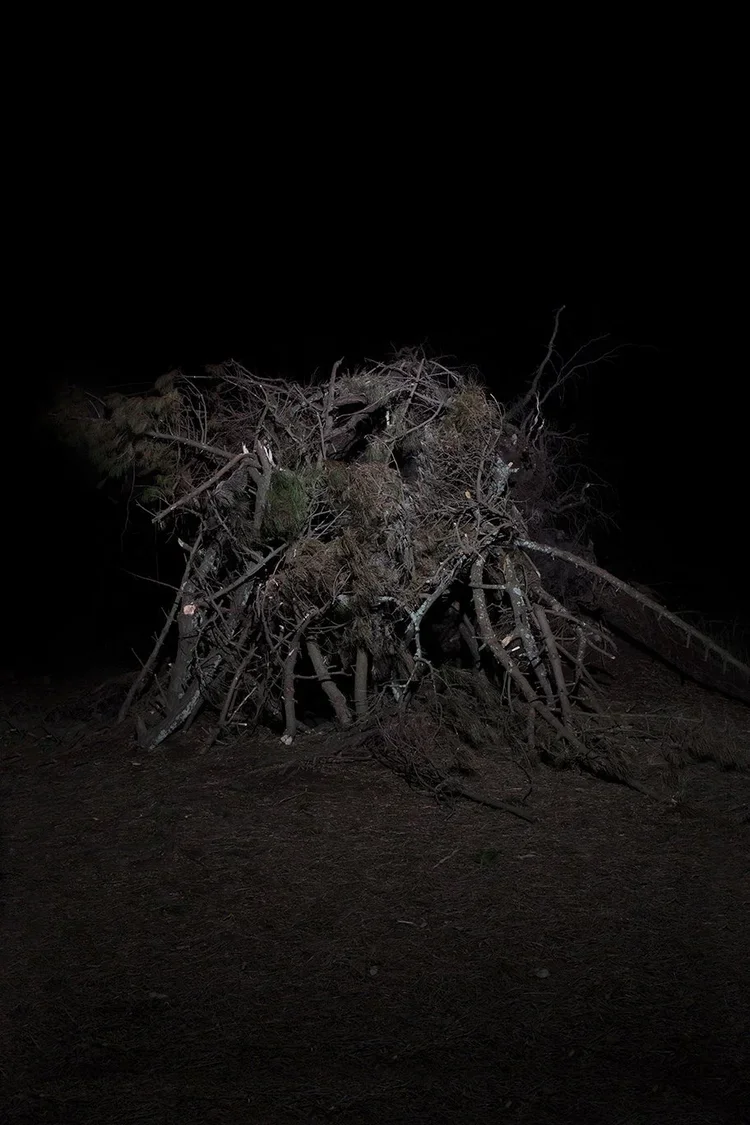

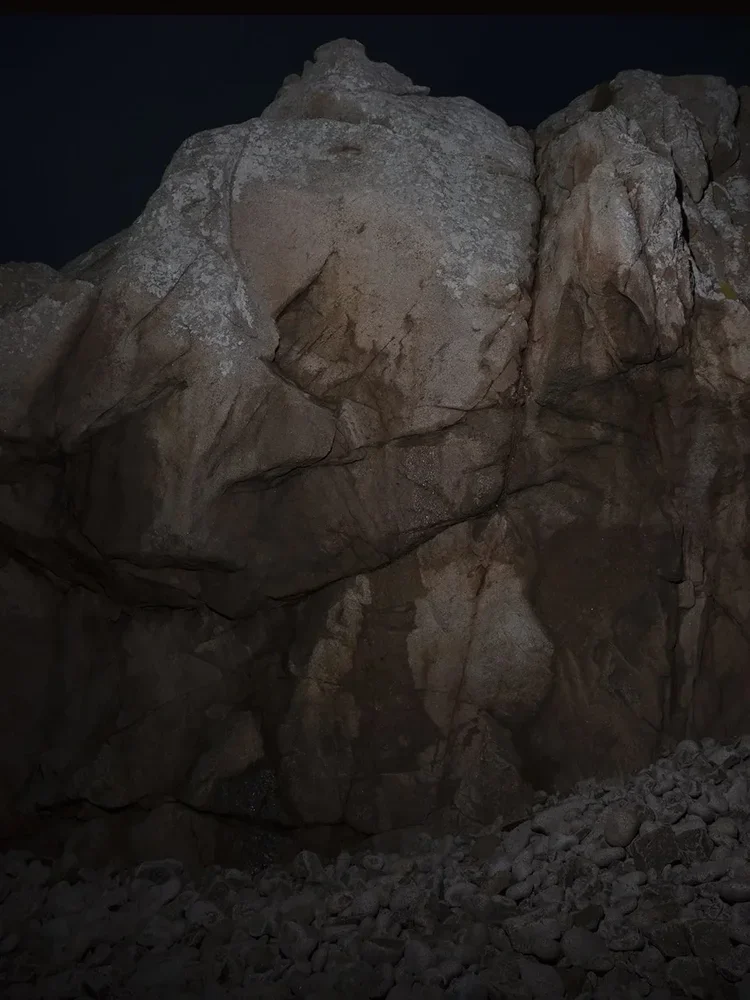

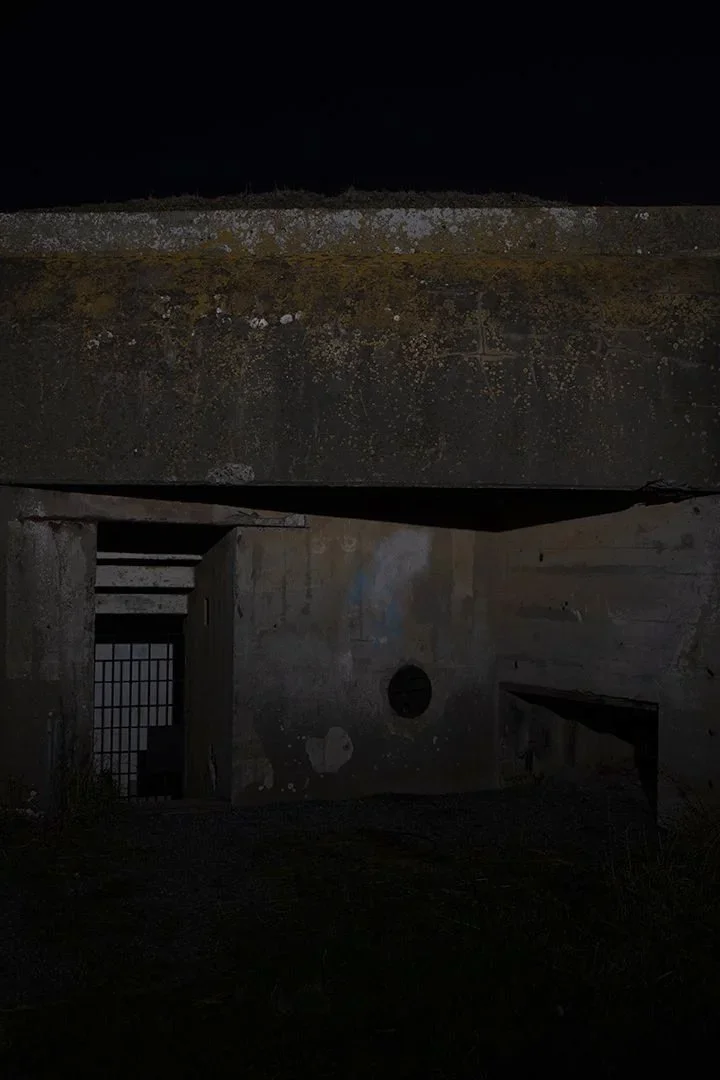

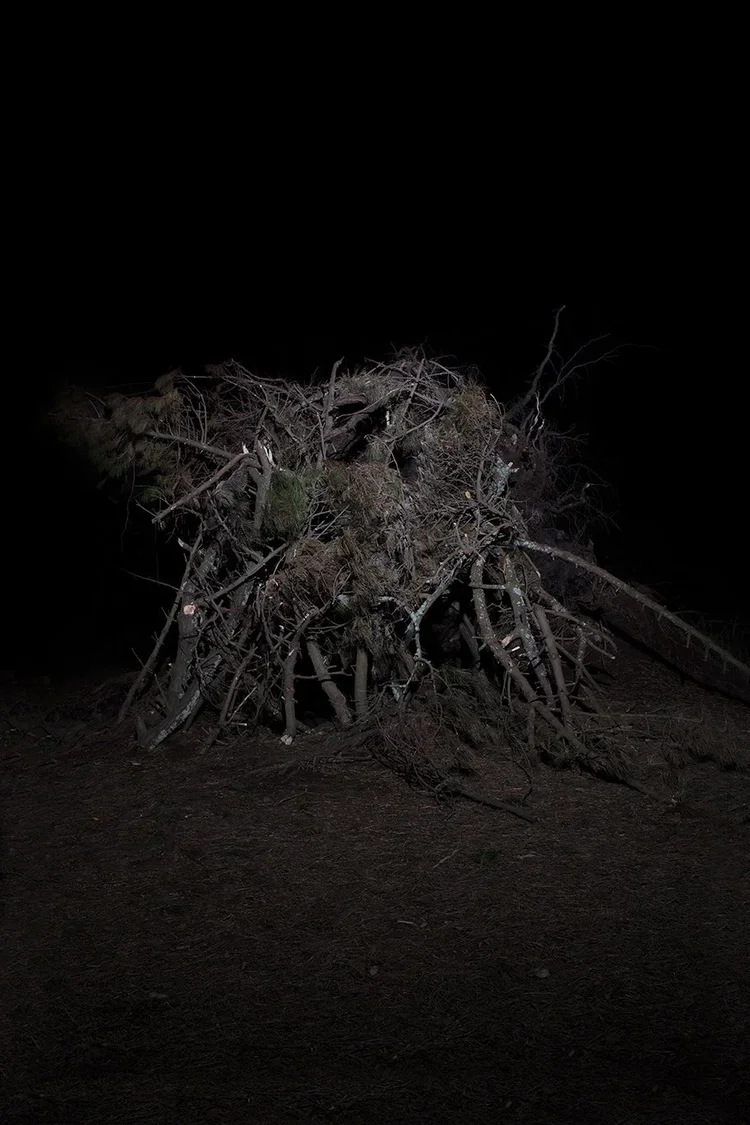

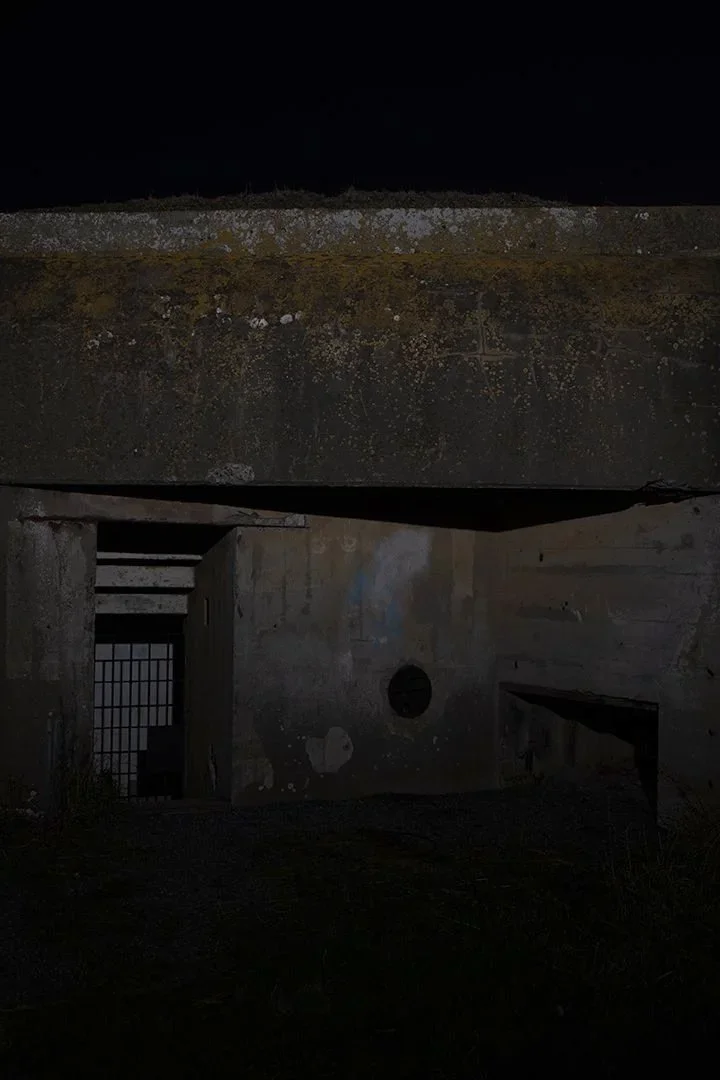

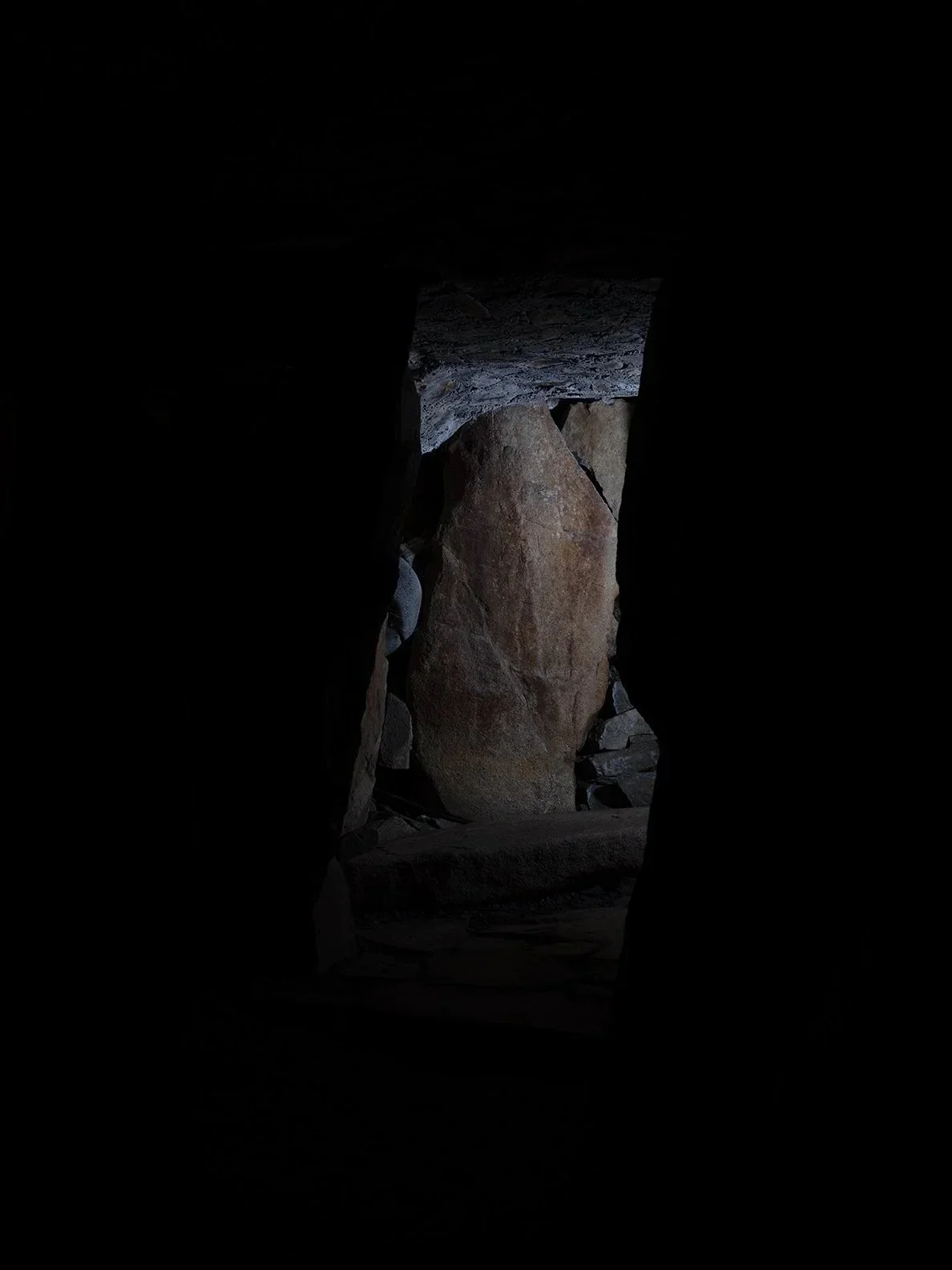

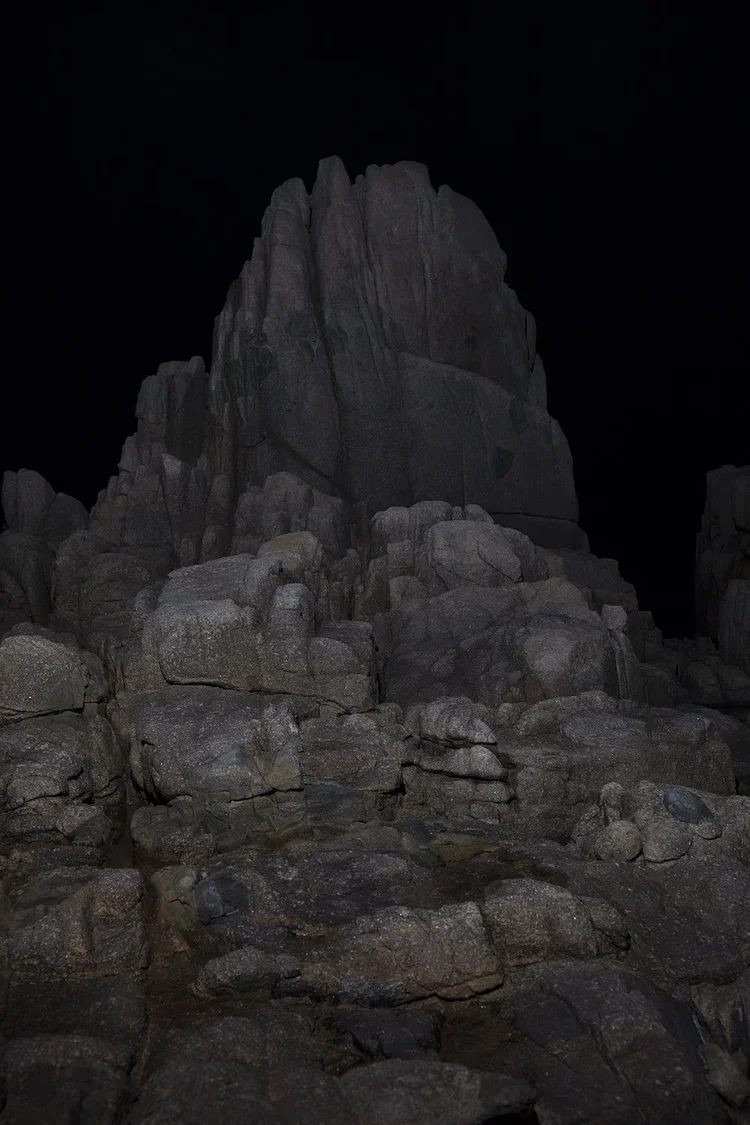

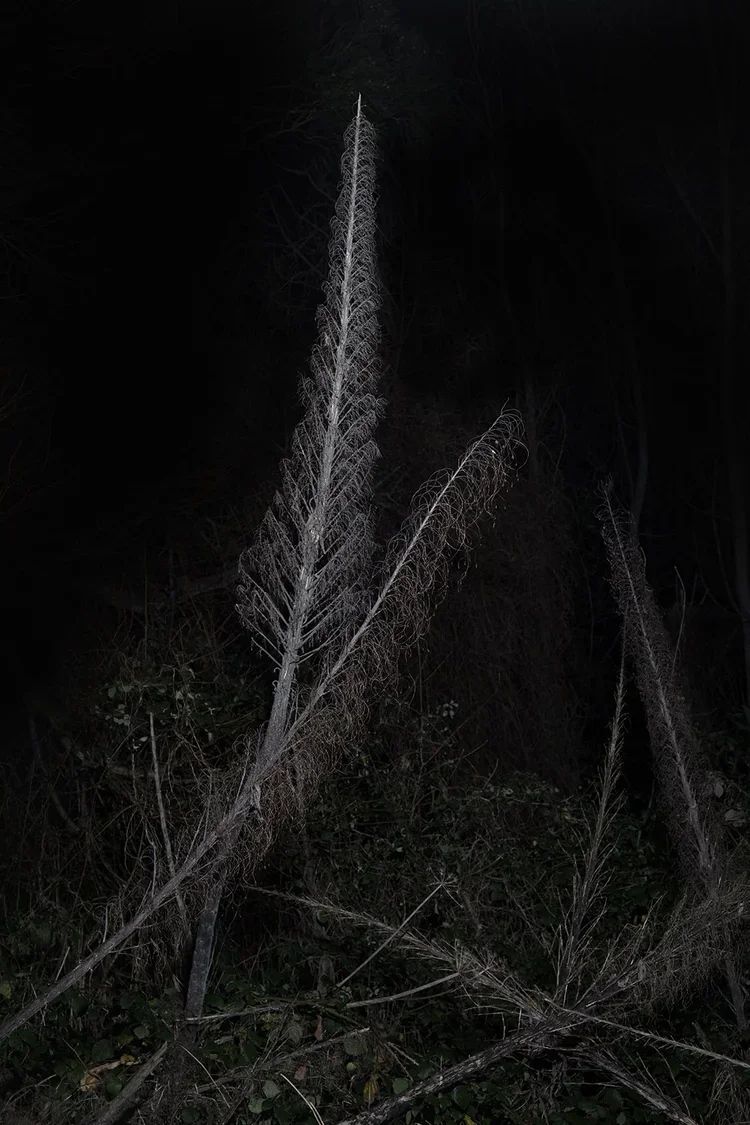

Aaron has been working on this particular project in Guernsey over the last four years, primarily in the autumn and winter months. All of the work is taken at night, and its subject matter ranges from images of isolated trees, overgrown hedgerows and rock formations, to man-made structures such as water towers, WWII fortifications and Neolithic burial chambers and menhirs.

As someone who is not knowledgeable about the history of landscape photography, the only way I could write about the project was to select a few of the images and try to describe how I feel about the work and why these specific images felt significant. I appreciate that this is a very subjective, and perhaps self-indulgent way of appraising the work of an artist and friend, but often, images contain so many ineffable characteristics that trigger a range of emotional responses that logic and the written word seem like blunt tools for trying to understand why they work so powerfully.

…….

Aaron said that from early on in his art education he knew that he had no interest in becoming a commercial photographer. Graduating with a BA in photography in 2001, he followed this a few years later with an MA in fine art as he wanted to make work that communicated his own personal vision and inner emotional landscape. His strongest influences have always been painters rather than photographers and he enjoys viewing exhibitions of painting, understanding intuitively what makes a successful work.

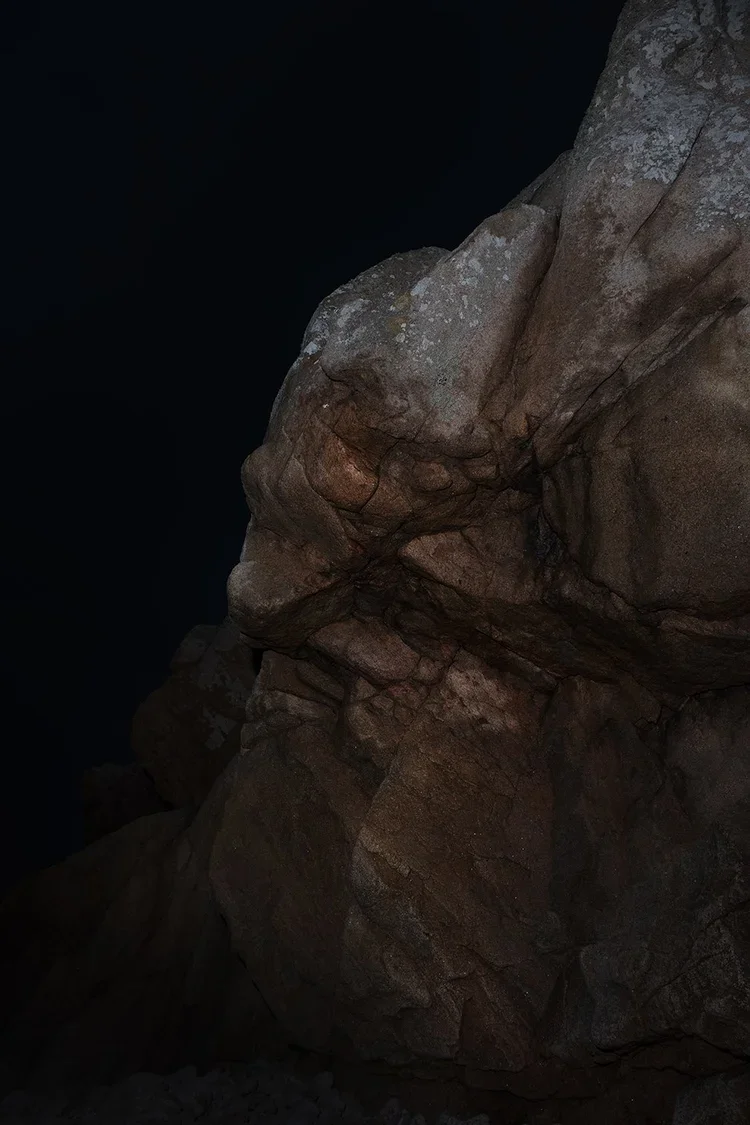

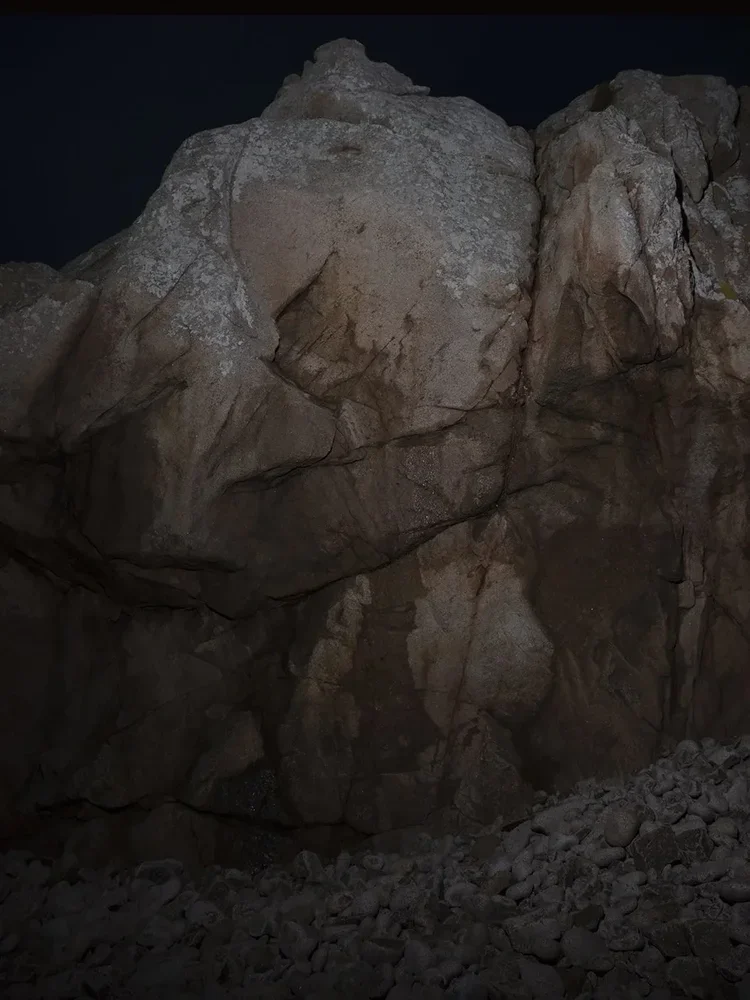

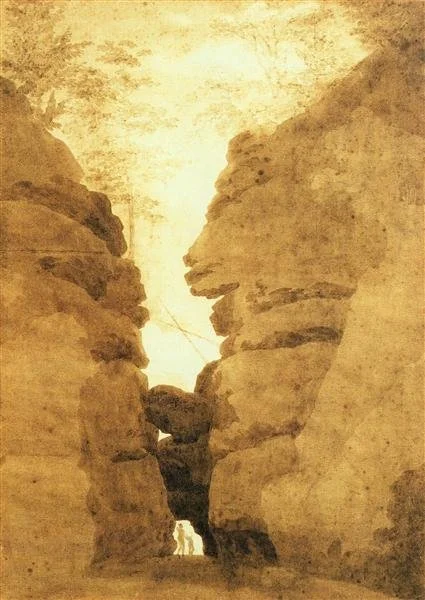

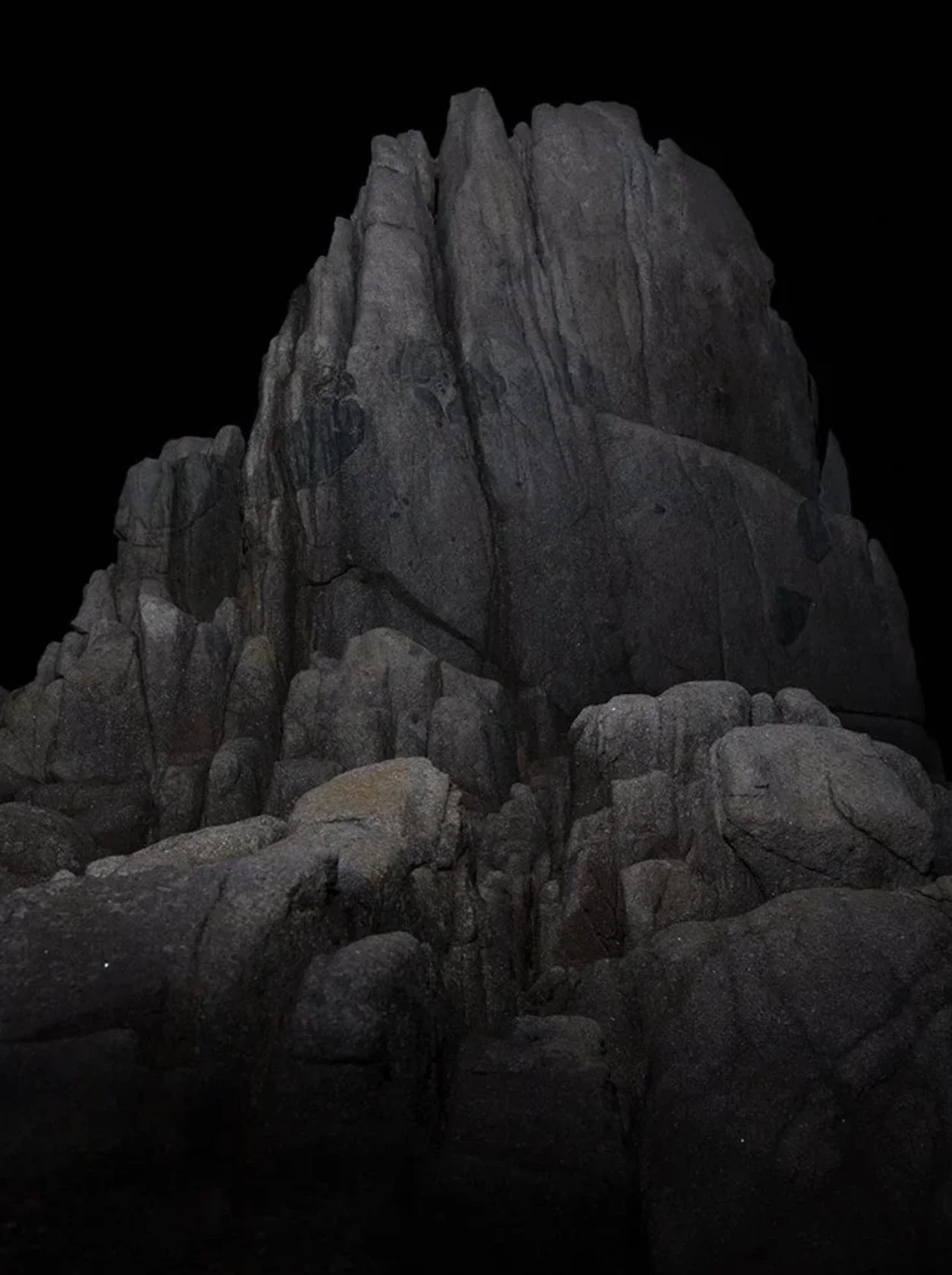

His favourite painter is Casper David Friedrich, the German romantic painter of the late 18th century and early 19th century. The influence of Friedrich is really palpable in many of Aaron’s photographs, particularly the rocky crevasses and eerie ruins. It is also there in the way he plays with scale and perspective to make the viewer feel a sense of awe, but also an element of confoundment, in not being able to quite work out how near or how large his subject is. Looming out of the darkness it is sometimes difficult to determine whether you are looking at a branch near the forest floor or a giant pine towering high above the human scale.

Above - Aaron’s recent photographs interspersed with paintings by Caspar David Friedrich.

Talking last week over lunch, Aaron told me that landscape work has always been a thread running alongside his better known work featuring people. He said:

“It is a natural thing for photography and landscapes and painting to come together. And especially in Guernsey. A lot of people here consider landscapes in Guernsey to be beautiful. And for them, that is what photography captures. Well, see, I don't do that. It's a whole different way of looking at our environment.”

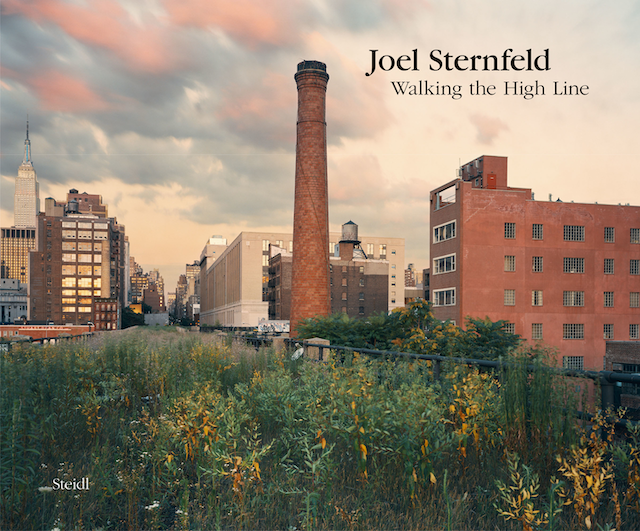

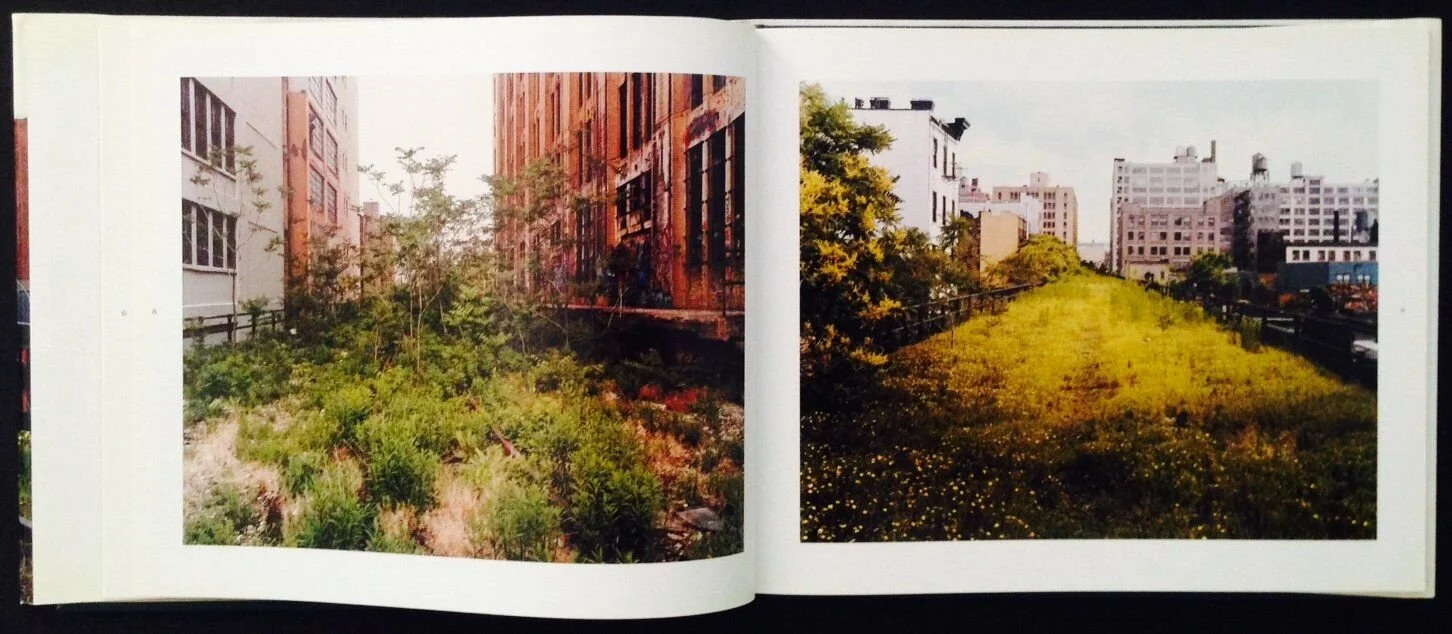

American photographer Joel Sternfeld’s project “Walking the High Line”, is a body of work that resonated with Aaron early on. This shows a derelict railway line and buildings in New York, photographed in the late 1970s. It is a forgotten commercial line of a mile or so in length. Aaron said “The rural had started to take back all the urban land, so they're really beautiful. It's kind of bleakish, but it's how nature's been reclaiming from man.”

Above - images from Joel Sternfeld’s ‘Walking the High Line’.

The Photographer, Gem Southam’s “The Red River” made in Cornwall in the 1980s, is another of Aaron’s influences. Southam captures the interconnections of industry and a manufactured landscape with the natural world. The Red River was considered to be a real paradigm shift at the time, when working in colour was uncommon, and his compositions and close up angles were very different to the norm. These images though were interspersed with traditional landscape imagery which were influenced by English Romanticism. His work contained the straggling ruins of Cornwall’s tin mining past as they slowly merged with the plant life and waterways.

Above - some photographs from Gem Southam’s ‘The Red River’.

“Southam saw the landscape as a confluence of its inhabitants and the valley’s primordial formation and ancient mythologies. The Carboniferous granite, Bronze Age adits, and medieval tales of travellers lost on a winter’s night, stumbling upon a solitary illuminated window exist in harmony within these photographs. The artist explores the concept of history itself in this series, which he sees concentrated within this river and its fern laden banks.

He drew heavily from the Book of Genesis for this project: a tempest over a dark sea, punctuated with white capped waves references God’s creation of light and darkness out of a formless void. Primeval elements of the landscape, foliage and the rushing of the river’s red water, reference the second day of creation. Bucolic idylls juxtapose representations of the despoliation of the Earth and its subsequent regeneration. Southam’s relationship to the English landscape was profoundly influenced by poetry, in particular works by Beowulf, John Milton, and John Bunyan.

Wandering throughout the valley and beside the stream, Southam recalled Milton’s depictions of Paradise, lost and then regained; images like Valley of the Barking Dogs, Brea Adit draw from the apocalyptic imagery of Paradise Lost, while others are akin to the beatitude of Paradise Regained. The photographer saw an allegory in his journey along the Red River that went beyond local history, something universal wrought within all of the valley’s shattered remains and ‘poisonous tang’, as he calls it, its beauties and redemptions.” Jem-Southam-The-Red-River-Press-Release.pdf

…….

Like Southam’s work, Aaron’s landscape series moves from the local to the universal; the sublime to the damaged. Although it fits into the category fine art photography, it also can be thought of as documentary photography.

This cross over in categorisation made me think of Mali Morris’s article on Robert Welch’s paintings, in a back issue of Turps Magazine (Turps Magazine Archive Feature). In this, she refers to the artist/photographer Walker Evans’ wonderful 1964 lecture titled “Lyric Documentary”. Walker believed that the addition of lyricism to the documentary style in photography added greatly to the work. He felt that “the lyric is usually produced unconsciously, and even unintentionally and accidentally by the cameraman, with certain exceptions. Further, that when the photographer presses for the heightened documentary, he more often than not really misses it. ” Walker felt that the term “documentary” “was inexact, vague and and even grammatically weak as used to describe a style in photography,… but it happened to be his style”. Walker Evans Lyric Documentary

In the lecture, he goes back in time throughout art history to define those artists who he views as the antecedents of ‘lyric documentary’, including Leonardo in his medical drawings; William Blake’ engravings illustrating ‘physiognomy’ in a book by Lavater; and Audubon’s glorious ‘Birds’. Walker says: “I find Audubon falls into this category that I call lyric documentary inasmuch as he was setting out to document the birds. At the same time he took such care …But he had a trick of scale which was remarkable that also harkens back to Vasalius who had a way of presenting his subject in a noble, heroic style, and it the background actually documenting, lets say, the waterfront of Charleston, South Carolina …which could have been used by a mariner sailing in there… The plan trying to make it is that this is grounded in the earthy and actual fact. At the same time it gives such a sense of beauty that you grow lyrical, or I do anyway, looking upon it.”

Aaron’s work documents the landscape and our human connection to our environment in a similar way, and, for me, its strength lies in this crossover of the documentary and the lyrical.

…….

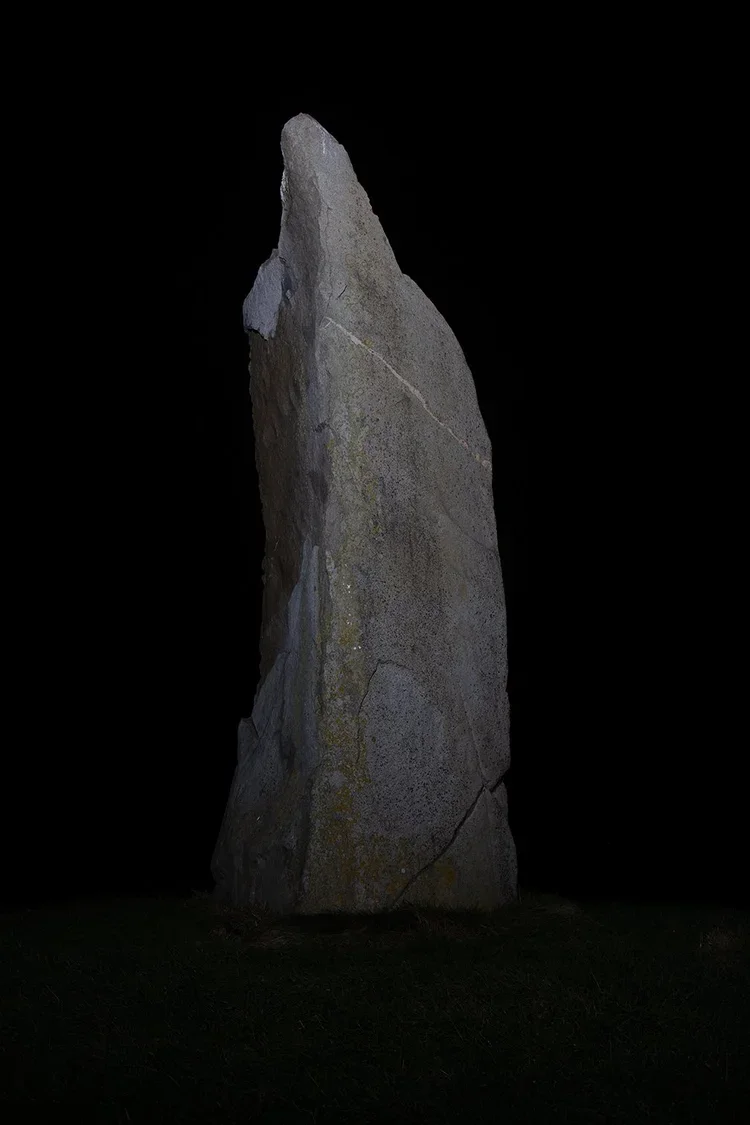

It was difficult to select a handful of photographs from the project to discuss as so many are visually impactful. One that drew me from the first time I saw it, is of the menhir that sits in the churchyard of Sainte-Marie-du-Câtel (also known as Notre Dame de la Délivrance).

Menhir, Sainte-Marie-du-Câtel church yard

The two metre high figure was found buried within the chancel of the church in 1878, about a foot below the surface. Archaelogists believe this happened in the sixth century when the first church was built on the site. The figure was found with her feet facing the east, in exactly the same alignment as many passage graves. Like the menhir’s St Martin’s cousin - La Gran'mère du Chimquière, the Castel menhir has also suffered damage. Its right breast has been chipped off, though it is not known whether this occurred when the statue was lifted from the chancel floor or whether it was done on purpose as a Christian rebuke to paganism of the past.

Although the breasts might indicate that the figure depicts a woman, menhirs were often masculine. They were placed at natural energy centres such as hilltops, headlands and carns in order to endow these sites with a sense of ‘placeness’. Neolithic people seemed to understand the significance of symbolism and create narratives around the magical qualities of the landscape. Menhirs, particularly those with anthropomorphic features were created as symbols of fertility sometimes involving rituals to bring about good harvests or childbirth; to ‘fecundate’ the earth, which was perceived as the feminine.

Most photographs of La Gran'mère in St Martin’s tend to sentimentalise the figure, which has carved curled hair. She is often presented with a garland of wild flowers crowning her head as a celebration of the spring growth. Aaron’s figure of the Castel Menhir emerges softly from the dark. It’s face is unreadable in its inscrutability, and the outline around the neck area could be perceived as a necklace, or perhaps even a long beard. The minimalism of the imagery highlights the texture of the granite stone and the slight curve at waist height is suggestive of human form, if not of gender. There is a comfort in the inky blackness of the image which somehow gives a sense of the dark unknowability of the past and the person or people who crafted the figure.

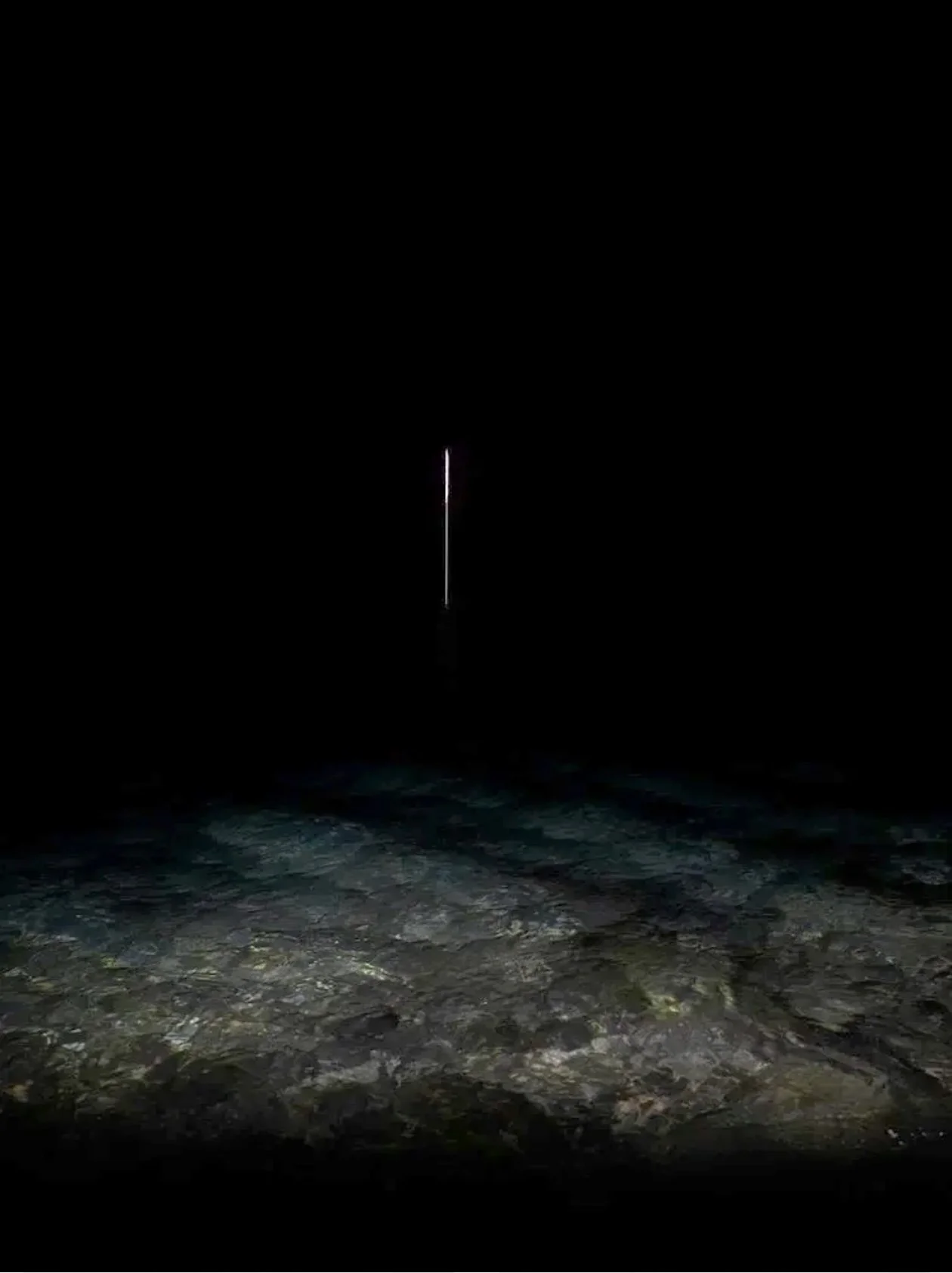

The second photograph (above) was initially shown as part of the Exile and Return exhibition in May 2025. It was one of six that were printed on aluminium and held upright against gravestones in St Pierre du Bois churchyard. Walking around this site before the private view with some of the exhibitors, most of us found this image both unsettling, and unfathomable in terms of its geography.

Imbued with melancholy, or possibly menace, it appears to show a vertical structure or shard of light glinting sharply out of the middle ground like a stainless steel needle. The foreground depicts shallow water flowing over an uneven grey-green surface of boulders, rocks and cement. As with many of Aaron’s photographs, it is really difficult to work out the size of the objects depicted, the scale, or the distances between the elements.

After many wrong guesses, he told us that the structure was the pole at the end of Rousse breakwater. This is a working pier on the north west coast, used by fishermen to land their catch. In the winter months it is frequently battered by storms, but is a popular year-round site for swimmers, particularly when the tide is at a point where the pier is fully or partially visible. In the dusk it is a common but eerie sight to see figures appearing to walk on water as they wander the 500 or so metres out to the pole at the furthest tip of the pier.

The photograph feels uncanny due to the clarity of the pole, which is often blurred by a shrouding of mist (or my short sightedness when swimming without my glasses). The shallow water swirling gently in the foreground and the way the object is lit makes it seem much closer to shore than it actually is. It appears almost spectral and otherworldly, but leaves a hazy sense of disquietude and apprehension.

Like a lightning rod within Walter de Maria’s “The Lightning Field” the pole seems to radiate immense energy. But unlike De Maria’s sprawling Minimalist sculpture, it feels singular and symbolic - a hermetic icon which has an unknowability that feels almost religious or spiritual in nature. While it is revealed here like a sudden lightening strike, the viewer has a sense that in its revealing, there is an impermanence. By dawn it will likely have faded - a half-remembered dream that lies just outside memory’s grasp.

Magnolia Tree

In the last few years, Aaron has displayed a number of images of magnolia trees that are common features of local parks and town house gardens - exotic splashes of colour brightening the dark months of February and March. Being further south than the UK, we rarely experience snow or long periods of frost so the trees have flourished, becoming sturdy, gnarled and ancient in many of the grand Georgian front gardens around St Peter Port.

Aaron’s earlier magnolia photographs seemed miraculously symmetrical. The magnolias’ fuchsia or white waxy petals glowing softly out of the dark depth of the gardens, their graceful outline indicating tight manicure over many decades.

The tree above fills me with joy. Like an anarchic dancer breaking free of the rigidity of classical choreography, its sharp upwards sprouting movement calls out to be noticed above the delicate pink curves of its tutu, frayed netting trailing towards earth as movement slows to a final flourishing bow.

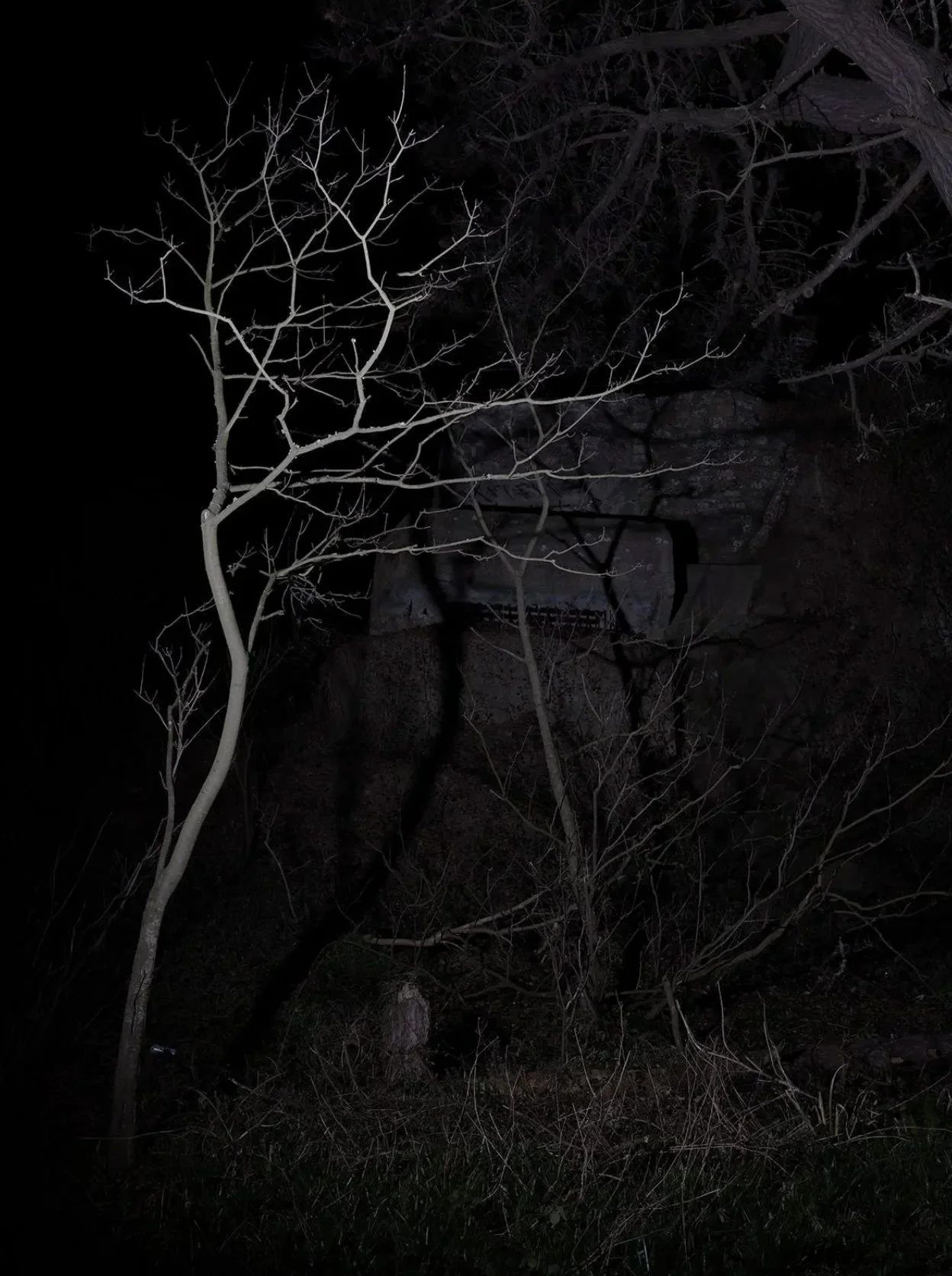

The Watch House at the Guet

The final image that I have chosen is the high precipice on which the Watch House at the Guet sits, with the later edition of WWII German concrete fortifications below. The fine tracery of a wispy sapling is picked out by Aaron’s lighting which throws a dark shadow on the granite and reinforced concrete cliff face behind.

All of Aaron’s work is shot in colour, but with the exception of a few works like the magnolia tree above, many viewers mistake these works for black and white photography. Because of the minimal colour, the work relies on strong composition and tonality for its impact.

I am particularly drawn to the more complex and less centrally-focused landscape images like this one. Its impact seems to grow the longer one sits with it. The eye is drawn from bottom left, up and across the image to the top right, then slowly across to the top left moving down and inwards into the receding gloom. Its power seems to be in the contrast of ancient and new; nature and the manmade; and the monumental and the ethereal.

In slowly absorbing and unravelling the image, this exploration seems to enrich the experience of viewing. While its meaning feels manifold, only a trace seems to be revealed - the key to unlocking it seems tantalisingly just beyond the viewers grasp.

Walter Benjamin stated: “Language has unmistakably made plain that memory is not an instrument for exploring the past but its theatre. It is the medium of past experience, just as the earth is the medium in which dead cities lie buried. He who seeks to approach his own buried past must conduct himself like a man digging. [...] For the matter itself is merely a deposit , a stratum, which yields only the most meticulous examination of what constitutes the real treasure hidden within the earth: the images, severed from all earlier associations, that stand—like precious fragments or torsos in a collector’s gallery—in the sober rooms of our later insights. True, for successful excavation a plan is needed. Yet no less indispensable is the cautious probing of the spade in the dark loam, and it is to cheat oneself of the richest prize to preserve as a record merely the inventory of one’s discoveries, and not this dark joy of the place of the finding itself." Selected Writings: Volume 2: 1927-1934, ed. Marcus Bullock and Michael W. Jennings (Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1999), 611.

Aaron’s landscape photography calls on memory to try to make sense of today’s complex and troubling world. As Benjamin distils so well in his beautiful writing, neither history or memory are fully graspable or fixed entities. By exploring place through art practice, individual and collective memory can activate the past in new ways; through looking, conversations, fragments of recollection or reinterpretation of archival material. These connect us through the constellation of moments in our memories that slip and slide into brief focus through the observation of an artwork.

Tying together the underpinnings of a joint exhibition

In the last few months, I have been making a body of work for a joint exhibition with the documentary photographer Aaron Yeandle. In trying to curate an exhibition that will show our work to its best advantage, it has led me to think about the differences and similarities in our work.

In the last few months, I have been making paintings for a joint exhibition with the documentary photographer Aaron Yeandle. The focus of the exhibition is landscape - the Guernsey landscape specifically. In trying to think how our work would fit together, it’s made me reflect on the reasons why we feel an affinity for each other’s work; on the work’s similarities and differences; and how our approach to landscape differs from many other local artists.

Landscape has always been a contested term, meaning different things to different people. In the west, it was only officially considered an independent genre in the 16th century, and one that was seen as inferior to history painting, portraiture and still life. In the late 18th century it came to prominence, during the rise of Romanticism. Many other approaches followed in the 20th century. Today, landscape is a vibrant field, with artists exploring diverse themes and incorporating media such as photography and film as well as landscape art, installation and site-specific work.

Compared to traditional art, contemporary landscape work is far less likely to be concerned with the picturesque. It can be used as a way of thinking about cultural, social and economic development, environmental degradation, urbanisation, displacement, ‘nationhood’, colonisation and warfare. Landscape is often deeply rooted in human experience, and it covers the urban as well as the rural, the decaying and derelict as well as the beautiful and sublime.

The term does not only apply to representation of the real. Landscape can be an imagined place; it can also be a psychological space conjured up via half-remembered dreams or reverie. It is often a potent carrier of memory and identity, as well as a conveyor of emotions, capturing and embodying how the painter or photographer feels in the world. This can be done through the use of evocation and metaphor, the symbolic, allegorical and the poetic. For many artists, landscape is a means of exploring the human condition and our relationship with the world and with other life forms.

At this point when the planet is so dominated by humans that its ecological balance has ended, images of landscape can sometimes make us view the world differently. We are living in post-natural times, in a world in which the use of fossil fuels has altered the earth’s atmosphere, our waterways and oceans are polluted by fertilisers, industrial waste and plastics, and intensive farming has depleted the health of the soil. It feels like a time when our ecology’s existence is on a knife-edge. Images of our habitus provide us with the means to locate ourselves as subjects in relation to ‘place’. This is never more telling than at a time when areas the world frequently hit by devastating floods and wildfires and remedial actions to address climate extinction are too little and too late.

…….

A couple of years ago, Aaron and I had a conversation about how our work often had a similar quality that was apparent to us and others, but difficult to pinpoint in words. We said it would be interesting to curate a show of our work if the right opportunity arose. I thought that exhibiting our work together would make our painting and photographs become even more ‘of themselves’ through the contrast between the media and the dialogue between the work. Last summer that was made possible when we asked Adam Stephens of the Gate House Gallery if he had any free gaps in his diary for 2026.

In trying to unpick why Aaron’s photographs and my paintings often seem to evoke a similar atmosphere, we have talked frequently, if haltingly, about why we make the sort of work we do, and how our work seems to connect.

Like Aaron, I do not focus on the landscape in relation to its picturesqueness. The typical views of west coast sunsets or the steep cliffs and turquoise bays of the south coast are, without doubt, wonderful, but they do not interest me as subject matter for paintings. We both seem to be drawn to the spaces that people walk past unseeingly; to the spots that many others view as eyesores. The taken-for-granted hinterlands where thistles spread rampantly, gossamered with spiders nests and dew.

Other areas of the island draw us as they hint at the sublime, but perhaps in a less pronounced way than the archetypal views of mountain crevasses or the ocean’s stormy abyss that the Romantic tradition is known for. The places that draw us are sites that appear to hold a darkness. They somehow underscore and intensify our sense of human fleetingness in comparison with the deep time of the rock formations and landmasses that they conceal. The knowledge that these sites existed several millennia before humanity provides a powerful lens for understanding human impact in the age of the Anthropocene.

It’s impossible to write about a two-person show featuring photography and painting without considering the relationship of these two media and their differences. Painting is a shifting elusive entity that flickers between what it is depicting and its ‘objectness’, i.e. its material embodiment of oil on canvas or watercolour on paper. Painting are one-off objects that are produced by the physicality and existence of their maker - through the impact of our senses and our memories, via the context of our own history. Their making involves layering and time. Once autonomous from their maker, or even before this, they flicker into life through being observed by a viewer.

Paintings involve mark and gesture. Making them is an embodied act and their meaning can, in part, be intuited through the action of painting or drawing which remains in the structure of their being, embedded in their surface and texture. The objects produced are records of the movements, emotions and spirit of their maker that have existed in time.

There is a duality between the ‘objectness’ of the painting and its way of creating space, pattern or colour field as virtual space. Painting is illusory, and often makes use of artifice through the use of perspective and representation, yet materially, it is made from the earth that we occupy and many of the same components as our bodies.

While photography is also made through the hand, the eye, and an evocation of the senses, it is captured through mechanical, chemical and digital means and can be used to make multiple versions of the same work. While the first examples of photography were set up to record reality, its traditional documentary and scientific function has moved in multiple directions since the early 1800s, one of which is contemporary fine art photography.

Photography is an accepted medium within contemporary fine art practice. It is able to adopt elements of painting, cinematography and performance and it plays with form, lighting, composition and narrative in similar ways to painting. Photographers regularly combine documentary and conceptual methods to explore personal yet universal visual themes, as can painters should they wish to.

Like painting, photography has an ability to capture elements of the landscape that reach beyond the powers of the eye. Photographs can both simultaneously be a means of expression and of investigation. A photograph is a frozen moment where time feels like it is suspended, but, like painting, it has the ability to make the familiar seem unfamiliar through the singular vision of its maker. This can be used to reimagine and represent the landscape in ways that displace the privileged human viewpoint. To the viewer, this can unsettle our centrality as subjects making us look again at what is in front of us, in ways that range from the startling and shocking to the gentle and slowing down.

Since the outset of photography, painters have made use of it, both as reference material for their work, and to illuminate their own practice by seeing the world differently post-photograph. Images from the archive are often used by painters (myself included) to tap into the pathways of memory and imagination. They can be used to release new meanings from the past that seem to have bearing on the present.

…….

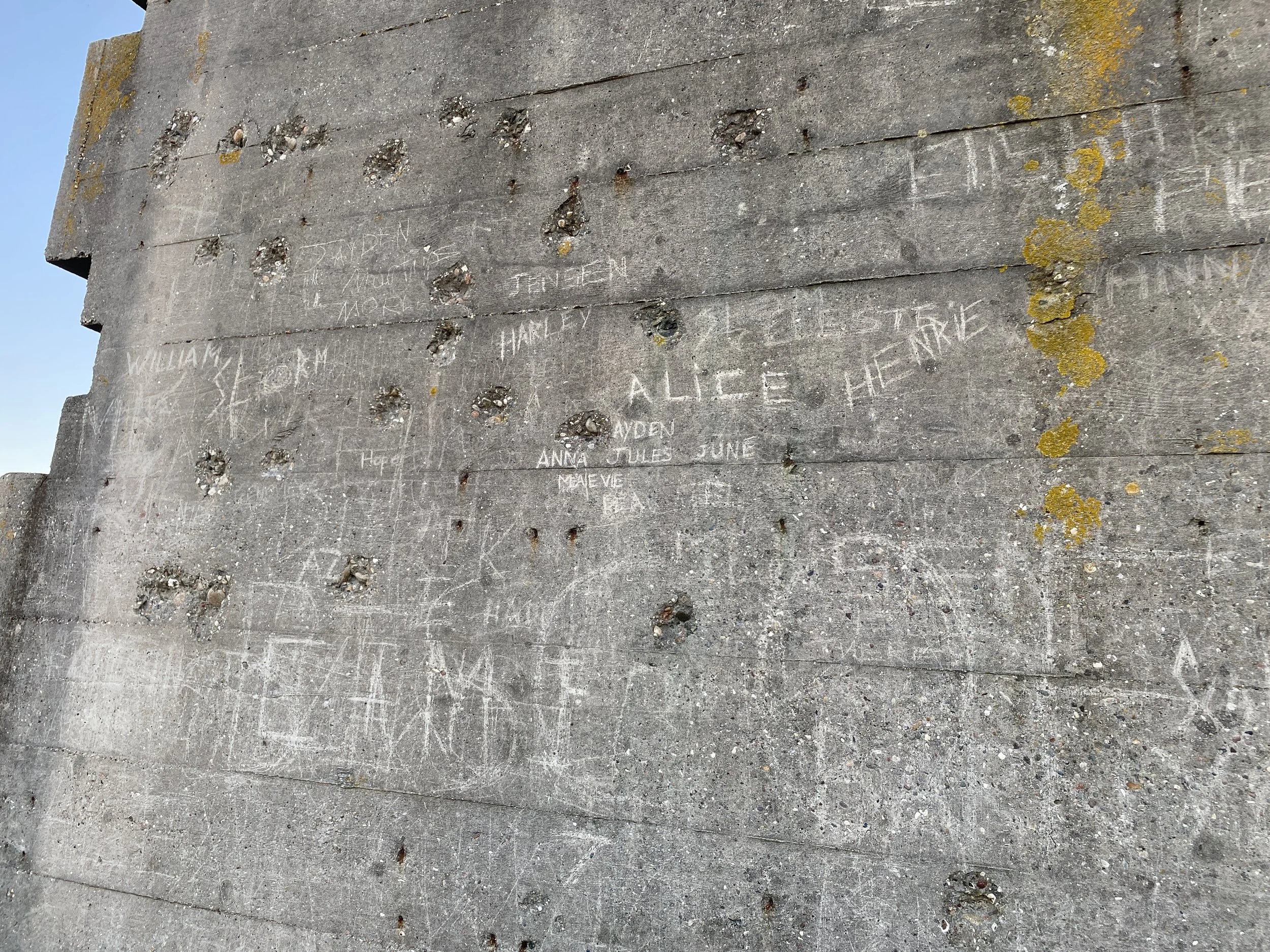

So often on a small island we travel the same routes, take in the same air and pass the same buildings week in and week out. In doing so, it is easy to fail to notice those commonplace constructions and artefacts that have become a taken for granted part of our terrain. The thousands of bunkers scattered across the landscape, their graffitied surfaces memorialising lost love; the corrugated walls of an abandoned flower packing shed empty and forlorn; or the rusting bulk of an industrial steamer, buried deep amongst bracken and brambles. Our painting and photography draws on these forgotten and abandoned sites that hold the weight and layers of our social history.

Sites of myth, storytelling and the sublime – the fairy ring and the megalithic burial tombs; the enormous coral granite headland at Albecq – still prickle the hairs on my neck, especially in a certain low winter light. Aaron who has lived here about 15 years said he feels an inexplicable darkness in Guernsey that lifts from him when he travels off island. Perhaps this is all I have really ever known, but I feel at peace with Guernsey’s shadowed vales and shrouded landmasses.

Aaron and I are both interested in the changes to the land and how history and industry shape it. This is a huge subject in its own right, which deserves more time and thought than is available now. Inevitably though, our discussion on the nature and changing face of the Island often moves on to how built up it has become. This is an enormous challenge to biodiversity, but it also impacts on the everyday pleasure of wandering the lanes and valleys – memories of which are signifiers of my free-range, nature-obsessed childhood.

The Island has become more affluent since the arrival of the offshore finance industry (or should I say, the affluent have become more affluent and the wealth gap has grown). This wealth is once again re-shaping the landscape. Huge mansions appear to spring up every few months, replacing modest bungalows and 1930’s family homes. Heading inland from the high western cliffs a few weeks ago, another new vast steel-framed construction appeared in my eye line - a looming skeletal brachiosaurus overshadowing the modest granite cottages of the hillside below. Change is inevitable and often positive, but it remains seen whether the growing wealth of the islands richest decile will improve island life as a whole, and not just be to the detriment of the ecology and the less well off.

While making a political statement is never the focus of my work or Aaron’s, and is not an objective of the exhibition, the political and social are embedded in our work, as they are in every part of life. What do we wish to achieve with this exhibition? I guess this would be for its viewers to spend some time with our work, think about the natural environment around them, and perhaps happen upon some of those everyday sites just through wandering aimlessly without map and viewing the island and its sister isles and islets with fresh eyes.

This post started out as a piece of writing about Aaron’s work and influences. Having been drawn off on a tangent, a bit like my walking habits, this will follow in the coming weeks so it can be given the full attention it deserves.

Second Conversation Planning Landscape Exhibition with Aaron Yeandle

Another conversation about our forthcoming exhibition. Here, we are finalising a grant application for the exhibition installation and trying to narrow the reach of the exhibition in terms of the subject matter.

FR I thought it might be useful to set some parameters or restrictions on what we include in the exhibition, if you agree. This would be really helpful for me because I always find it quite hard to narrow down what to cover in an exhibition, if I have some control over the subject matter. I mean, I don't want to limit you, but I just thought it'd be quite useful to discuss.

So I thought, looking at your work and what you've done already, it's got to cover World War II architecture, the German architecture and bunkers, etc.

Aaron Yeandle from Occultations series

Megalithic sites, do you think?

Megalithic Burial Tomb, from the series Occultations, Aaron Yeandle

AY Yeah, yeah.

FR And I was thinking, I’ve been making work for a while that is to do with edgeland or hinterland …for instance, the abandoned greenhouse and horticultural sites, so that would be important to include. I don't know if you've got any of those?

Fiona Richmond, from a body of work on the Salt Pans

AY Yes. Yes, yeah, I do, yeah.

FR You've got rock faces, cliffs and caves. Well, you haven't got caves, but you may want to have caves. You've got individual trees and bushes.

AY Yes. Yes. Yeah, so that can be included, and all that type of stuff.

FR Yeah, and then, I mean, I quite like the idea of flower paintings, as carriers of memory or memorial. I might put in some little canvases of tiny wildflowers or that kind of thing. And I know you've got some, but you weren't sure whether to include those or not. And that's obviously up to you…

Aaron Yeandle, series on Guernsey’s indigenous plants

AY Yeah. Yes.

FR But I guess it kind of fits within this framework, doesn't it?

AY Yeah.

FR And I thought even I might do the odd one where I've got an outline of an animal or animal bones, feathers, animal hair, that kind of thing.

Rabbit Remains in Herm, Fiona Richmond

And I thought my ruling out criterion for this would probably be no humans except traces of human through the land or through buildings and ruins.

AY Yes. I see.

FR You know, how the land's been shaped by humans and obviously the...

AY Yeah. That covers all the architecture, that covers all the flora and fauna, all the weird little bits of land that we find interesting that we capture.

FR Yeah, but no actual visible humans, as in no depictions of humans, if that makes sense. But I don't think you've got any anyhow, have you in your photos linked to this project?

And I mean, I just thought if I've got those parameters to start with, once I've done a bit of work and you've obviously got loads of work already, but what we can bring it together and discuss in a few weeks to see what direction it's going in. Because we've got the three rooms, it could be split into three areas.

AY Yes.

FR areas of work, but you know, I'm fairly open as to how we do it or how we display it.

AY Yeah. Suppose I think it all depends then on the edit, you know, once you're finally happy with what you've been doing over the next few months and then I suppose like say, when is it, January, February, March. So let's say then, come February-ish, we could sit down and do an edit maybe.

FR Yeah. Yeah.

Well, maybe late January, do you think? We can get together, look at where we are and, you know, I can just take photos of where I'm at, bring those along to you and we can sit down with the imagery together.

AY Yeah. Yeah.

I mean, obviously, you know, by then I'm going to have a shitload of stuff. But of course, I'm only going to be showing a small amount of that.

FR Well, this is it. I mean, I think you, I mean, your work you can always use in other exhibitions, can't you? So...

AY Yes. So as long as it's like an equal equilibrium of our work together, I think that's really important.

FR Yeah, yeah. Oh, definitely. It doesn't even have to refer directly to certain places, but I suppose, you know, as we do when we curate, you look at colour, you look at...the commonalities, you look at the differences, and that will really come together through the curation, won't it, I think.

AY Yeah, definitely. I mean, already there's a few that I think, well, okay, those are like winners already. But you know, I've still got like the whole November and December and then January, got three more months of shooting.

FR Yeah. Yeah, well, you, you're on fire at the moment; you seem to be out doing stuff every night.

AY Well, I knew the rain was coming, so, in that sense, I thought I made the effort, although I was a bit slack last week, but I still went out, and, but of course, I will be gone for almost two weeks now, so...

FR Okay, yeah.

Yeah, yeah. So you're making the most of it before you went.

AY Yeah, yeah. It kind of gives me the chance to have a look at it. So I popped it on my website now, all the stuff away from the Skype stuff, all in one folder thing called ‘Occultation’. Yeah.

FR Oh, okay, so I'll just look at that folder and if, I don't know if they'll need any imagery for the exhibition grant application. I might put one or two images of paintings in or something.

AY Yeah, definitely.

FR So if I pick a couple of those from yours, I mean, if there's work that you want me to put in specifically, just ping me an e-mail with them attached along with your updated CV.

AY Yes, I’ll send stuff tomorrow then and then I can go through it tomorrow evening. I've got to go and judge this photography competition in the evening. So at least I've got tomorrow afternoon to look at it.

FR And then I'll send it to you either… I've got work tomorrow evening, but probably I think I might take Wednesday off. So I'll send it to you by Wednesday lunchtime. And then you can read through. And if there's anything you want to add, change, etc.

AY Alright, perfect. So, at least that gives me Wednesday afternoon to look.

Then, by Thursday, I'll be gone.

FR Yeah, yeah, I mean, if need be, if we need to tweak it, I can always send it to you, but I guess you may not be have good Wi-Fi access where you are.

AY Yeah, the only Wi-Fi I'm gonna have is when we're in the pub, so majority of the time I'm not gonna have much much internet.

FR Yeah, you won't. Yeah. But I don't think it's going to be too onerous to get this together really.

AY I mean, ultimately, you know, we can add more to it if you think and you need to do framing and stuff. But of course, if we're going to do the workshops, we need to be paid for that too. So we need to add that on. If you wanted to, because you could do a workshop where we just go to some beautiful key places and do a sketching afternoon or something.

FR Yeah, well, you put what you normally put down for that sort of stuff in terms of costs and I'll just, I'll mirror that with what I put in because I haven't a clue about what to charge for things like that.

AY Yeah.

FR Yeah, and I'll put in about doing workshops, maybe a guided tour or some sort of talk about our work. Yeah.

AY Yeah, the main cost is printing the prints and you know I may not even mount them because that is a whole extra expense.

FR Yeah, I think it would look fine. I think it would look lovely actually, just and if you've got some large transfers too that you can, you know, stick directly to the wall.

AY So...Yes, yeah, maybe like one big one.

FR But some of them, some of them you probably want to pin so that you can have the option to sell them.

AY Yeah.

FR Or however you do it, bulldog clips or whatever.

AY Something like that. So that would keep the cost down and, you know, that's not crazy nowadays in an exhibition either, because you know, if anybody knows anything about photography, it's the cost of mounting and printing is the show, isn't it?

FR Yeah.

And I think these days, I think it's quite, it's quite acceptable, more interesting even, to show work unframed.

AY Yeah, and, you know, when I had that London show the other day, and when I went there, it was all pinned on the wall and stuff like that. So, then if you are just like sticking your canvases up, for example, without framing, then that may have a connection then.

FR Definitely, I wasn't planning framing, apart from maybe some of the small ones. I was planning on just having... unframed work, but I might also, might have a little bit of an installation because if we're doing some work around the salt pans. I've got some little pressed glass, Victorian glass salt cellars, you know, lots and lots of them. I thought if I could use one of the windows, put some glass shelving up on the windows all the way up and put them on there, you'd get all the refraction. Sort of linking in the landscape of the salt pans to the domestic...

AY Nice, yeah.

Yes. Yeah, well, that sounds lovely.

FR But again, I don't think that's going to be massively expensive. I just need to buy some reinforced glass for that.

AY No.

Yeah, well that sounds good.

FR Have you ever bought reinforced glass?

AY Well, I mean, I’ve bought Perspex a lot for... because it's cheaper.

You can buy it down to cut already, perspex.

FR You can, they'll cut it for you, will they?

Oh, that would be handy because it's not heavy, the pressed glass.

AY No, and Perspex is lighter as well, than reinforced glass - is quite expensive. We use Perspex a lot at school.

FR Yeah.

AY Yeah. Perfect. That’s exciting then.

FR Yeah, I think it's coming together. It's just more... I suppose I just needed to be a bit clear about where I was taking it at this stage.

AY Yes, and ultimately, it's about the nature, the like the weird macabre bits of nature that Guernsey is inhabited with so much. Then obviously the historical buildings, megaliths and Neolithic.

FR Yeah.

And with nature, I suppose it's about the history of the sites and the change of use by humanity and then almost about nature claiming that back in some way.

AY I made some legends to support the work.

And kind of the ghostly remnants of that being left behind for.

FR Of, of, yeah, in terms of the occupation stuff.

AY Yeah, it seems quite macabre the work we do, to a certain extent, and it's not the first thing when people go out and do a landscape, is paint or do what we do. And that's the thing, it’s about looking at our everyday environment with a different view of a landscape and what actually that landscape means to us personally.

FR Yeah, because neither of us are interested in pretty chocolate-box landscapes, are we?

AY Exactly. And even though yours is colour, mine is still colour. There's hints of greens and in there, so I so I think that will work. It will lend itself really well.

FR Of course, it's colour, yeah.

And I...I'm going to do some big...black and white charcoal stuff and also I'm trying to do some more work that is much more using a very limited palette. So although there will be... patches of brightness, a lot of it might be quite low key.

Fiona Richmond, from Salt Pans work

AY And I think that both the low key and the brightness route will really bounce off the night time stuff, I really believe so.

FR Yeah, because yours has got, it's got this sort of luminosity where you've got the, like the trees or architecture coming out of the darkness, hasn't it?

AY Yeah, so that will really lend itself to your colour palette that you use.

FR Yeah. Oh, I think it's coming together quite well, don't you?

AY Definitely, I mean, I'm not worried about it at all. I think the key thing now is just to make the work, keep coming back together every few weeks. And once I'm back, maybe if you wanted to come to, see this really interesting rock formation, is just on L'Ancresse. If you go past Pembroke as far as you can go and you go around a sharp corner and it's not that little bay, but there's parking just around there. There's some really interesting rocks we could go in the evening.

FR L’Ancresse, yeah. Yeah, I probably need to go in the day as well to capture them in the day, but I guess if I come with you at night, I'll know where they are then.

AY Yes.

Oh yeah, or even early evening before it gets dark and stuff.

FR Yeah, it's getting dark pretty early now, isn't it? I think the clock's going back next weekend.

AY Oh yeah, so you'll be dark.

FR Yeah, but I mean, I can go at the weekends anyhow, you know.

AY Yeah.

Yeah, definitely. So it was really interesting rock formation around there. Quite unique to the other interesting rocks.

FR Yeah? Cool, because I haven't done any rocks for ages and I'm a bit nervous about doing rocks, but I need to get back into them…

AY And these are like monsters and things, so it's really interesting.

FR Yeah, I love your blood monster tree as well. Where was that?

Aaron Yeandle, from the Occultations series

AY Oh yeah, dude. Well, I have to give you that print. It's around the corner. I just noticed it when I was coming up the lane. I thought, I'm going to have to find out where that is.

FR Ohh, I know, can you drop me can you drop me a pin with that and I might go and do a painting of it?

AY Well, it's kind of on the edge of a farmer's field, so it's totally fine for you to go in there. But I went in to see, I went to the farmer's field and found it, and it's in part somebody's house. So I went to the wrong house, and this old child came out. So I told him, he said, oh, it belongs to them, they won't mind. So then I went over and spoke to them.

FR Ohh. Yeah.

AY But fingers crossed with all the wind and stuff, it should still be there because it is actually some type of vine over the main tree. Yeah.

FR Oh, okay. Wow, sounds brilliant.

AY But you go down the road, like a couple of minutes down the road from where I am now.

FR Yeah, I don't know whether I'll find it without you, but...

AY Oh no, I would have to show you for sure.

FR Yeah, yeah. Right, well I don't think there's anything else. Can you think of anything that we've forgotten...

AY Well, I know, send me the application, then I can have a good look on Wednesday.

Um, and then I think, and then I'll probably be like out of... contact for like a week and.

FR Yeah, yeah, well I hope you have a lovely trip and it'd be nice for you to catch up with your Map mates.

AY Alright, fantastic. And any questions or anything, you know, I'm always happy to hook up and have a chat and stuff.

FR Yeah, lovely. Okay, well, enjoy the rest of your week and I'll catch up with you. Well, I'll ping you the e-mail, you know, all this stuff, and then I'll speak to you when you're back, I guess.

AY Yes. Alright then. Okay, you take care. Bye.

FR Take care. Bye.

Upcoming Exhibitions

POSTCARDS FROM THE ARTIST STUDIO

“Postcards from the Artist Studio” is an exhibition that will be held at Both Gallery in Highgate, London from 20th to 26th October 2025. It features new postcard-sized works made by members of the Split Collective, which I’m involved in.

Split Collective is comprised of around 70 painters and sculptors from Ireland, the UK, Europe and the US, who have been on the Turps Banana Art School Correspondence Course and Onsite Programmes during 2023-25. The members got together through a common desire to strengthen bonds and to support each other’s creative work.

This exhibition brings the Collective together for the fifth time in 2025 with a fresh show of our smallest pieces. Postcards have been an integral part of our exhibitions as a means of fund-raising for the exhibition costs, but we feel now that it’s time to show our small works in their own right.

Do get along to the Both Gallery next week if you are near enough. It will include a great mixture of affordable art.

Exhibition: 20th - 26th October, 12-4pm

Private View: 23rd October 6-8pm

Both Gallery, 323 Archway Road, London N6 5AA

Clockwise from top left: Hillside pathway in Herm to St Tugual’s Chapel, Fiona Richmond; La Gran'mère du Chimquière, Aaron Yeandle; Lost Ground, Battery Mirus, Fiona Richmond; Tree Root from the series ‘Occultations’, Aaron Yeandle.

A COLLABORATION WITH AARON YEANDLE

I’m currently working towards a two-person exhibition with photographer Aaron Yeandle which will be held at the Gatehouse Gallery in Guernsey. We have been working together on this project for a couple of months, and it is due to open on Friday 27th March 2026, running until 19th April. Do pencil the private view in your diary on the evening of 26th March!

Aaron is a documentary photographer who has won and been short-listed for several national and international photographic awards. While he is probably best known for his portrait-based work, he has a real love of landscape photography. Since I returned to painting in 2020, we have taken part in several group exhibitions together, discussing and enjoying each other’s work. We felt that a joint exhibition would work well, highlighting our similarities and differences.

Over the last 18 months, Aaron has been capturing a body of dark and mysterious nighttime images that have been made across many of the transitional and marginal spaces in Guernsey. Like me, he draws on the past to think about the relationship between human life and the environment using landscape as a vehicle to consider what it means to be present in the world at this moment in time.

My own landscape work is not presented as a scenic depiction but as immersive; a series of marks and signs that focus on the fragility of life, both human and non-human. Drawing in the landscape is often my starting point, recording both what I see and what I feel. It makes me think about past events - the memories, people, stories and landmarks that have shaped us over the millennia. Although I’ve lived in the island most of my life, the topography has changed dramatically since my childhood, affected by increases in population size, average wealth and the changing lifestyles of the community. Capturing the here-and-now feels particularly important at the point where the co-existence of humans and nature has tipped drastically towards destruction.

Aaron and I hope that the work being developed will provide an opportunity for viewers to reflect, slow down and make their own connections to the images. Many of us feel disconnected by the deep undercurrents that fuel our existence, and the best way to form hope is by feeling a real personal connection and relationship to land and landscape - to the community and the ecosystems we are part of.

Thinking About a Two Person Landscape Exhibition.

I’m just about to start a joint project with photographer, Aaron Yeandle which will culminate in an exhibition in April 2026. As it’s the first joint show I have done, I spoke to Aaron, and we agreed that it would be a really interesting to document the process, recording our discussions as we went, and seeing where the journey took us. This is the first discussion we have had since securing a venue for the show.

FR I suppose maybe we should start with why we thought showing our work together in a joint exhibition might be an interesting project. Maybe you’d like to start?

AY It was your idea, I'm sure.

FR Was it?

AY Yeah, I think so … so why do you feel like our work fits together well?

FR I just think there's a real affinity in that, although you're known for your portraiture work, your landscape work is also a really big part of your practice, as far as I can see. And because it's really haunting and it has that same sort of slightly uncanny feel and darkness to it that my painting often has: a sadness and a sense of place, or sense of loss or memorialising about it perhaps...

AY Oh, yeah, I mean, I have to say, at the moment, especially over the last couple of years, I've been preferring working on those landscapes, than doing the documentary stuff. I'm a bit bored, to be honest of doing portrait projects. It’s not boring in itself, but I feel like I've done as much as I can achieve in that type of project. I've still got a few things I would like to do, but I guess personally, as an artist, I feel like I'm getting a lot more from photographing those landscapes in the evenings.

I’ve just been out by myself, in the middle of nowhere, connecting to the environment wherever I am, on the rocks or in the woods. And even sometimes I'm waiting for the light to go down, getting there a bit early because I like to look around and stake things out for locations. I'm just sitting there waiting for it to get a bit darker, in that time that you are sat by yourself, it’s that mystery time, dusk time.

Photographs from Aaron’s Scarp Project. More of his work can be found at www.aaronyeandle.com

Yeah, it's cool. Quite magical. And also, because most people would be photographing in that period of time, they call it “the golden light”, that's what the photographers say. The golden light is that period before dusk and darkness where it's like a really beautiful light, even cold light or warm light, depending on the sun and the time of the year. And I'm waiting to get into that darkness, but it's that quiet little moment of time before I get up to start making work. I'm just thinking about the environment, all sorts of things, being an artist, and that's why I enjoyed finding that moment to myself.

When I’m doing those documentary projects, it's hard work. It's really hard work, in the sense that you have to work with so many different types of people. And don't get me wrong, it's fantastic. And I have the opportunity to just spend time with these people from all different walks of life. It’s quite special. But I think, through some parts of your own life, you need to, as an artist, make the work that makes you feel something as well. Definitely, yeah.

And I think in those landscapes, there is some connection for sure between our work and how we see. It’s as if we use two different media to make work of the same essence. And also, it's quite autobiographical to some extent, in that we put our own stamp on it.

FR It's definitely about our inner worlds as well as our surroundings isn't it? Distilled into the landscape.

AY Yeah, definitely.

FR And I think, just as you say, walking and sitting in the landscape on your own is such a powerful feeling. You feel very much more connected and grounded than in everyday life.

AY I think it would be good to use that list of local landmarks that Helen provided as a starting point. But then just freestyle it, you know.

With my MAP6 collective next trip, we're going to Knoydart, which is the last wilderness section of the whole United Kingdom.

FR Where's that?

AY It's right on the west coast - it's a tiny little peninsula. You have to get a boat to it from Scotland. It’s not far from Fort William. We go there at the end of October. And some of the group have spent ages doing weeks of research and stuff and they've already got a good idea of what they want to achieve. Others of us, including me, take the opposite approach. I just want to go to that environment and let that area talk to me somehow, and for me to interact just on that pure basis of feeling it, and, you know, that's quite a risky thing to do, but other people are feeling that they want to do the same. Even the documentary photographers from MAP6 are thinking that they’ve had enough of that approach and want most just to be in that environment, in that landscape.

FR So is it about moving away really from an academic approach to documentary photography in terms of that research element, to a much more intuitive way of working?

AY Intuitive, but then afterwards, you start writing a bit more academically once that work or that place has actually spoken to you and then you start bouncing off each other and they manage to put things together. Text as well, afterwards.

FR So, yes, you're part of a collective as well. How have you found that?

AY I got involved a while back, before COVID. So, what, five, six years?

FR And do you find that having that collaborative group approach is a helpful, lovely thing alongside your individual work?

AY Yeah, I think it's really important because, I think with the particular art that we make, I'd find myself making the artwork alone in the landscape. And I think to be able to have a trusted group of individuals that you feel you can be yourself with, with no egos, no self-centredness, and really work as a group, but share the skills, attributes and knowledge that we have openly to help each other. I think is is fantastic. And you really start to grow as an individual artist, but learning to work with other people I think is key. Like us, just being ourselves, we can sit here and talk about anything. And through that, then our work really blossoms. In the collective, none of us are feeling ‘I don't know if want to do this project, because that person's a complete dick.’ It could be a good thing to be working on. Yeah. But ultimately, that's never going to work out well.

FR No, you have to feel an affinity and trust, don't you, with the people your are collaborating with? That's important.

AY And look, we've both worked for organisations and groups, over the years, where that hasn’t been the case. And that's why in the end, all those things were good learning experiences. Yeah. I learned a lot from those experiences, actually. Yeah.

FR Definitely. I’ve learned too from working with difficult characters over the years. And how important it is to trust your gut instincts about people as well.

AY Definitely. Yeah.

FR So what, I mean, in terms of the collective, what was the connection between your work. What pulled you together as a group, what would you say is the most important element? Because I mean, I guess you're both documentary and fine art photographers…

AY I guess it all started when maybe five or six of them had just finished their masters down in Brighton, and to keep that momentum going, they made this collective. And then over the decade it's kind of just grown into its own identity really. Ultimately, it's about people and place. If you want to do documentary work, you can do place, landscape, cities history, whatever, but it's that interest in our everyday environment really.

FR Yeah, because in some ways I suppose place and people are always interconnected, you can't separate them easily can you really? Place is shaped by people and people are shaped by place and community, along with other factors.

AY And I think a mission statement and set of values that underpin the collective were important too. It’s about sharing. Sharing the skills or knowledge, and being really open to that. And you know, that's quite a hard thing to do, because you get used to working by yourself. Yeah. But ultimately, it's so important. It's refreshing to be not owning that, just letting it be free, because you get so much back in return actually.

FR Yeah, so I suppose in terms of some areas there's an element of compromise, but with other things, you kind of have more of a say.

AY Yes, it’s always compromise, because you can have 10 people involved in making a photo book, and there's going to be 10 different opinions. But it's about thinking of the greater good of what the outcome is going to be. Yeah, so I think it’s important just to let go of that control sometimes.

FR Yes, definitely, I think that's something that we're both quite good at, working collaboratively. Having sort of worked with you before on group exhibitions, you've got so many skills that I don't have in terms of practical know-how, and a brilliant eye that is needed for the curation and hanging of work, which I've got absolutely no recent involvement with.

AY No, but your painting over the last few years, your technical skills, your eye and your instinct, is fantastic. And you've also been working with your collective of painters and sculptors.

Pathway Through Sea Beet and Wild Flowers to Nazi Stone Crusher

FR Yeah, over the last year. Yeah, that’s been amazing.

AY You would have learned a lot from those people.

FR Oh, I have, yeah, and continue to. It’s been brilliant.

AY You know, however long you've been doing it, you get to see how different people exhibit work and their thought process behind that.

FR Yes, they've found very different ways of hanging with Split Collective. In terms of the first show, which I didn't sadly get to, it was in a huge empty supermarket in Wrexham. It was massive and had lots of really rough walls with extra boarding put up. They had a lot of space to hang, so it was curated very sparely in clusters of work that really worked well together, and a lot of variety in size and genre due to the broad nature of the group. And then we've I've done other shows where it's been much more of a salon hang where every element of the wall was covered because we didn't have so much space, but it was still very considered.

But I think it would be amazing to work using some of your photography blown up on the walls and to treat it as an installation with some of our work interacting. As you suggested, with some of my paintings or drawings overlapping your prints, and perhaps even some of your prints encompassed within my painting. Screen printed perhaps?

AY It would be great to make some outdoors work too, to put around the grounds, rather than just thinking of the exhibition as being the three rooms of the gallery. It might be interesting to show your paintings outside. It could be so cool.

FR Yeah, it would be interesting to do work as you do with your outside work, on aluminium, maybe photographed and printed, but then also apply some paint to it. So that it’s a reproduction of a painting, but made into a new work through direct application of paint.

AY I would have thought you could paint on aluminium really well.

FR Yes, lots of painters use aluminium as the substrate for painting, but it's just whether it would degrade in the outdoor environment. I’d have to do some research.

AY What about acrylic? I mean in the sense that it's perhaps better in the elements?

FR I don't really like working in acrylic, I’ve always got on better with oil paint. But I think there are some acrylic paints that you can virtually paint on anything with. I suppose I've always been against using it as essentially it’s a form of plastic, and at the end of the day many sources of oil paint are much more natural and less polluting.

I think. It's interesting to have works though that are shown in really odd, unexpected places as well. I’ve always loved Phyllida Barlow’s early work where she would suspend everyday things like a supermarket trolley from a street sign or something similar in a suburban street. But obviously we can't do that in the College grounds… and as I don't really work with supermarket trolleys on the whole… but it would definitely be good to display work around the school grounds.

AY And, you know, we would only need a few, two each, maybe.

FR Yeah, and different sizes as well would be interesting wouldn't it? Like a really intimate tiny work somewhere quite hidden.

AY Yeah. And then play to the landscape, look at what that landscape is about in their grounds and, well, think about what would work. … And we can do some workshops.

FR Some talks maybe?

AY Yeah, and I’m happy to go into schools because I've got the time to do that. So we could go to sixth form and maybe some other schools. A bit like we did when we did the Photography Now exhibition with Adam. We went in to do some to talks for 40 minutes about being an artist. Just about what you've done and what it’s like to be an artist. Those things are really eye-opening for students.

FR Yes, definitely. And it's good to be led by their questions in a way as well.

AY I've got to do a talk next week, next couple of weeks, I'm going to do a talk to the six form students about my practice. Also, it's good for us to talk about our work. It can be a bit uncomfortable at first, but it’s important learning. You learn so much actually, from it, it’s an important part of our practice.

FR Yes, I agree, and I think, if you kind of ask people what they see or enjoy, or find unsettling in your work as well, that can often be really interesting because it throws new perspectives on the work. I think that the artwork is not really the object, it's that moment of communication between you, the work when it becomes separate from you - a thing-in-itself, and the viewer. So, what they make of it is as important as what you make of it. And you're having to justify your work in a way to an audience which is also challenging but important.

AY And that's what's nice about how I feel about my work now. I don't have to justify anything to anybody. I make the work that I want to do, that I feel I need to do as a practitioner at that moment in time. And I made that connection with that process a long time ago. Yeah. Because otherwise you just cannot move forward and make work that’s really from the gut – that’s purely from you.

FR I also think it's important to share critical thinking amongst people around you who are really serious about their practice, which is perhaps lacking overall here at the moment.

AY Yeah, I’d be keen on being involved in more of that. And I don’t think it is important what medium you work in, it is just getting a group of people together that gel and are happy to work collaboratively, where it’s not just about ego.

FR I think what you bring from other aspects of your life into your art practice is really important too. In terms that we've both had to do a variety of jobs in life, often not glamorous, to support our practice, haven't we? Or in my case, a long period of not painting at all.

AY I mean that is very true, and very important. I think its a very different experience for people who do not need to earn a living who are artists.

FR But working alongside an art practice is not always a bad thing. The work I do in social policy, it's made me rethink a lot of things. Yeah, it's changed the way I think about the world, and also my art practice. The work I make now is very different, and differently motivated to the work I was making in my twenties.

AY It’s certainly different to sitting on a beach in Thailand drinking. You would have less need to make work, because you’re totally chilled out and don’t have any need to express stuff. With living in Guernsey, I's a different kettle of fish… it makes makes me angry at times.

FR Yeah, I do find Guernsey a struggle at times - it's a love-hate relationship. I love it because it's where I grew up and have memories, and its beautiful still on the whole, but it's frustrating politically at times.

Lost Ground: Battery Mirus (2025)

AY Yeah, it's also that sense of entitlement that some people have. It's about power. Yeah. We can address that in some ways in the exhibition, maybe.

And even those images I took that on my phone, I like to put them in the show somehow. Yeah. I don't know if you remember seeing them? They look like weird spirits coming up out of the darkness.

FR Well, it's nice to have a quirky element to an exhibition, isn't it? And I like the fact that you use, like in your shows about the native language speakers, lots of personal objects and ephemera that belongs to your sitters as well. It added a very different dimension to the installation of that exhibition. I've always wanted as well, in a show, to bring in other elements that impact on the senses, you know, things like certain scents or sounds. I know it sounds a bit weird.

AY Smells of places are quite potent in terms of it's a memory spark, aren’t they?

FR Definitely. I mean, sense of smell is such a trigger. I don't know how you would do it, maybe something like gorse flowers. Things that bring in the scent of the outside, and specific places in the islands into the gallery space would be good. And maybe see if Keith would lend us some of his sound equipment.

AY That's very true. I'm really open for us to exhibit whatever we think would add something. I want us to just let go and find this beautiful organic process. Definitely. Soil or earth or rocks in the gallery, one end. Yeah, definitely. I'm totally open … I don't want it to be... conventional.

FR I want to show you the Salt Pans as well at some point, which is the site round the corner. Historically it was used for panning salt when Guernsey was two islands. It was when the land there was the estuary between the two islands. The salt industry goes way back. I mean, there are implements in the museum that show that panning salt has been here since Neolithic times. But it's amazing now because it's this vast area of rough ground covered in pampas grass. It just takes over an environment, but it's also really interesting meadow marshland still, with amazing birdsong at dusk, the thrushes are incredible. And so many wild plants! And they're going to build social housing on it soon, which is much needed. But I'm kind of mourning that land in a way before its been lost, because there's such biodiversity there…

The Salt Pans

I was talking to Theo online a while back about the Guernsey language and the work with the arts that he and Matt are involved in, in trying to keep it alive. And there's a young guy who they worked with on their films in the past – Yannick - who's fluent Guernsey French speaker. I know his mum and he's very interested in botany and is compiling the Guernsey French names of all the wild plants in Guernsey. So I thought it would be good to do a field study of all the plants in this place, other than the pampas grass which is SO not indigenous, before it's turned into concrete. I thought it'd be so interesting to get the Guernsey French names of all these plants as well. Yannick is compiling them so that they don’t get lost.

AY Sounds good. It’s depressing how many of these plants are being lost to our environment.

FR It is. Right, before we both get too depressed, let’s have lunch and I’ll show you the Saltpans.

How archival imagery and painting can work together.

Summer is my favourite time of year, so I find July and August good times to reflect - both on life, and on art practice. I suppose, like many of us, that I am still trying to fathom out the direction my work is travelling in.

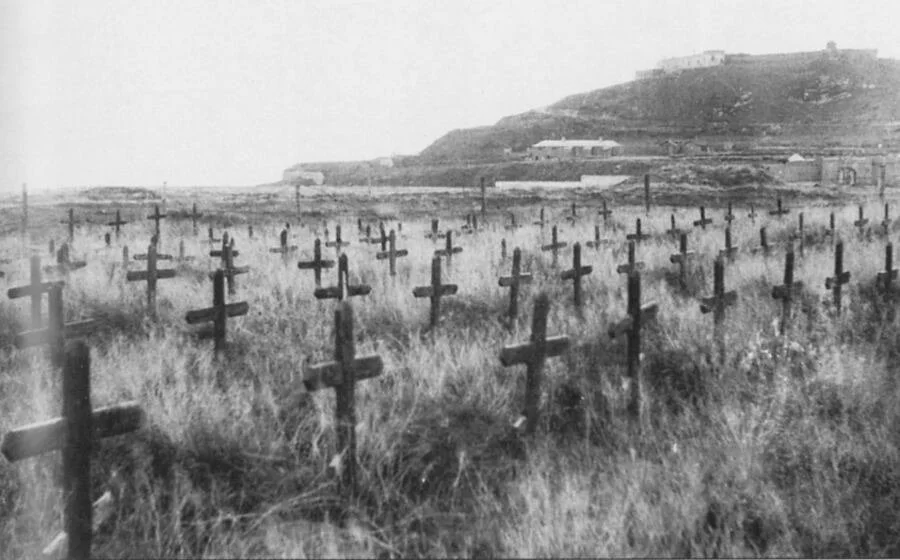

Archive material is something that I have used only recently to develop paintings. This was in relation to the local group exhibition “Exile and Return” which was put together in order to commemorate the 80th Anniversary in 2025 of the liberation of the Channel Islands from Nazi occupation during WWII.

It has made me reflect on how we collect and curate our own personal archives throughout life - photos of friends and family, festival tickets, travel passes, stones collected from memorable places. They carry traces of the past into the present, to memorialise, re-imagine and make sense of our pathway through life.

But what is archive? What is its purpose? How does it relate to fine art practice? What is included (and excluded)? Who defines it and who does it overlook, hide or obscure?

The National Archives describe archives as “collections of information – known as records. These come in many forms such as: letters, reports, minutes, registers, maps, photographs and films, digital files and sound recordings.

Looking back, it seems that from around 2005, it became more common for contemporary art and academic discourse to focus on the archive. I guess this is possibly linked to technological change with increased use of the internet, and no doubt, the digitalisation of archive material. Work from this period seems to be connected with social practices such as commemoration, memorialising and observances of rituals and traditions.

Archives both work as places to store records and as catalysts for memory. They are often drawn on to commemorate important moments in history. Artists, haunted by past events, or trying to make sense of current political or ethically charged events, often engage with archives as sources of material; they may use them for research purposes; or even to consider the concept of archival memory in its own right.

In his book “an Archive”, Edmund de Waal reflects on this further:

“Archives are purposeful and they are random. They record the personal and the institutional, plural and singular histories. They are passed on, inherited, stolen, plundered, and lost. They are destroyed by accident and by design, They record rewritings, rethinking, retellings. They hold stories so they don’t disappear. They preserve information in the hope of a future. Archives cross all of the senses. They are tacit, digital , somatic, auditory.

These are the archives as places of memory.”

The archive can be used to consider the relationship between time, history and memory, and the ways in which we understand the passing of time in relation to the archive itself.

Here’s a rather random set of images that maybe aren’t so random.

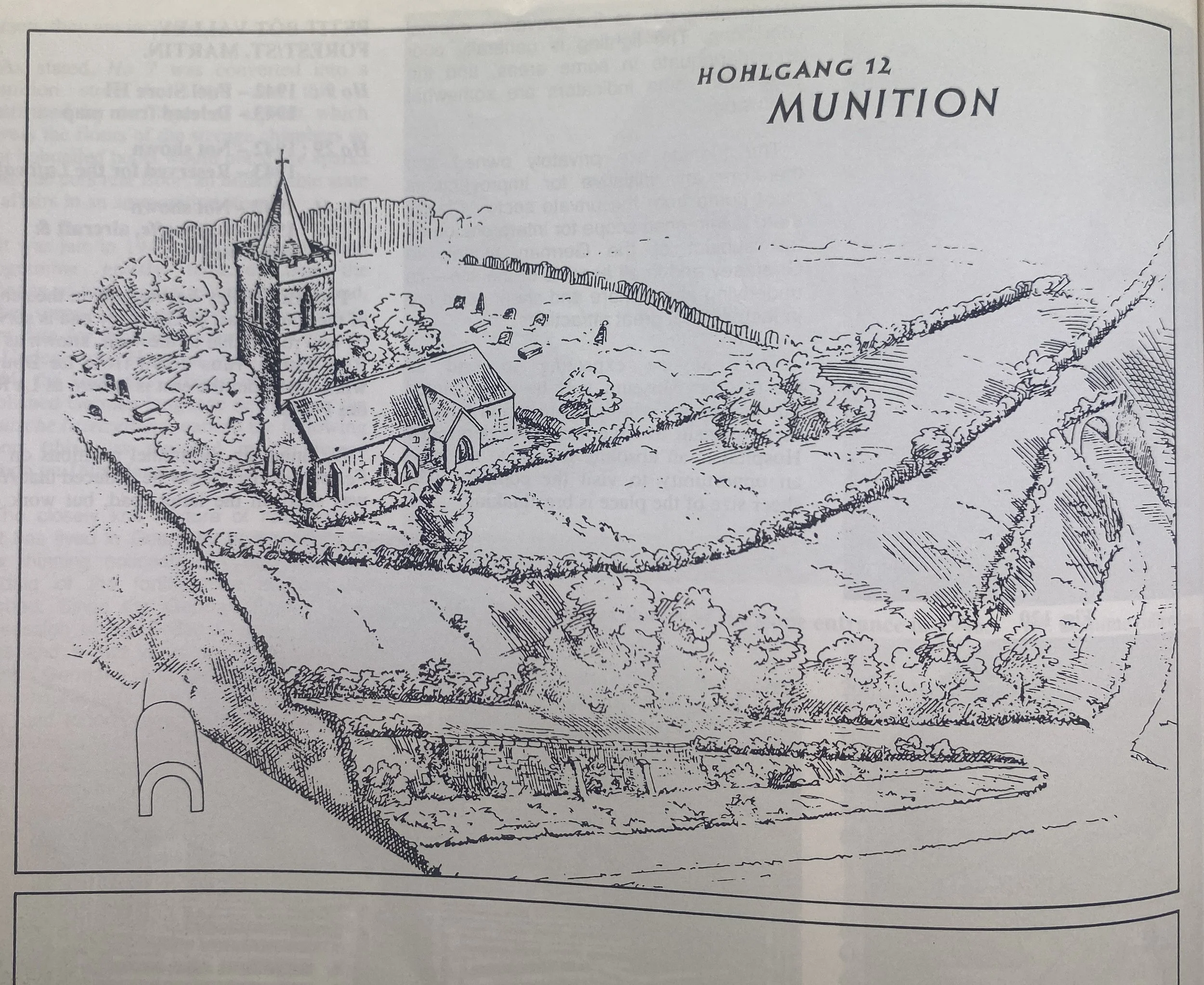

Diagramme of the German tunnels under St Saviour’s Church from WWII; My maternal Great-Grandmother’s Identity Card from WWII; Graffitti on the German Stone Crusher on L’Ancresse Common, used to crush stone for the cement used in fortifications; My Dad swinging over a German bunker in my Grandparents back garden; Sketch of the Vale Castle Guernsey, by John Mallord William Turner (1832); Burning of the huts that housed the Organisation Todt workers during WWII after the island had been liberated; Elliston’s Butchers - my Great-Grandfather, Grandfather and Uncle’s stall inside the Guernsey Market, 1970s; postcard of the Isle of Sark boat; my friend Ollie’s Grandmother - Guernsey’s last washerwoman, My Grandmother, Mother and Uncle; La Gran’mère du Chimquière, a megalithic monument outside the entrance to St Martin’s Church, thought to have been carved at two separate times - at around 2500 BC and then again during the Gallo-Roman period around 100 BC – 100 AD; A photograph taken by my grandfather in the 1950s of houses being built at Jerbourg, showing how much open land there was compared to today; Summer - the cat supervising baking; My late friend Stephen Palmer in his many guises; flag iris in St Peter’s Valley, Guernsey; orchid fields at Rocquaine Bay.

In making art, it’s hard not to reflect on the inescapable brevity of our time in the world and our relationship to what has been before and what comes after. The sheer timespan of visual representation from the cave paintings through to today’s art world sometimes feels overwhelming, if always a source of joy, awe and contemplation.

With the dire situation of climate emergency, and so much conflict, war, displacement and uncertainty around the globe, there is perhaps a need to explore if and why the nature and role of painting is still a relevant form of representation for the 21st century. It somehow feels important to do this, rather than just continuing blindly to make more imagery in a world that is saturated with the visual.

History and place is the ground for all representation. It is dialectical. We cannot escape the fact that we are all constructed in the specifics of a place and time; the beings that we are, are formed through our histories, personal and collective, yet we are simultaneously the makers of our own history. We are all situated differently due to the structures of our social environment, yet we are also actors in the world, who need to dream and to see possibilities for change and for the future.

Painting and drawing feel like apposite ways of considering the limitless possibilities in life and the elements of chance and action that form it. The fleeting contingency of mark-making with charcoal, pigment and oil embraces experiment, destruction, loss and transformation of the creative object. They are connected to us bodily, as a fleeting moment in time, both through the markmaking and the organic nature of their makeup. Markmaking is both intuitive and reflective, involving both thought and action.

Above: Moulin Huet Bay painted by Renoir; A phograph of a local jellyfish - once not seen often locally, human actions are making life easier for them. As vertebrates are disappearing (mainly due to overfishing), invertebrates have greater opportunities to occupy their niches. Huge jellyfish blooms may also be due to rising ocean temperatures and decreasing oxygen levels due to global warming; Wild allium on the headland at Port Grat; the German stonecrusher at l’Ancresse Common; Summer sea mist at Rocquaine Bay; Waving or drowning? Underwater swimming.

The constant laying down of paint or charcoal, erasing, rubbing back of paint and remaking, seem to be the material counterparts of personal memory and of the collective memory that we label ‘culture’. One could also draw analogies with the political recollection and construction that we name as history.

Memory and history make us who we are; the depiction of our worldly condition. Making visual art is confounding but it also understands that within life there are so many unknowns amongst the knowns; so much contingency. Art is not bounded by empirical, verifiable views of the human experience within the world. Artists get that. They understand that the measurable is insufficient to capture human experience. Art is therefore so valuable in exploring and expanding on the understanding of ‘what is’ and how we might understand ‘what exists’ or ‘what could be’.

The Enlightenment struggled for reason over beliefs and passions, science over superstition. The victory of reason was also misapplied to compound the issues of the pre-modern world. One outcome was colonialism which exploited and subjugated people across the world. As Walter Benjamin wrote: “There is no document of civilisation that is not at the same time a document of barbarism.”

This statement is a rebuke to the philosophy of historicism - the idea that history is made transparent through the gathering of evidence (dates, events, documents). That history is chronologically linear and narratives that mirror the past as it happened are faithful and correct, and constantly move in a progressive trajectory. This view of the world diminishes the role of human agency. It accepts the official records of history, without acknowledging the fact that those in power are the ones who shape the history books.

Looking back at history and using archive material within the creation of art is generative. It allows us to mesh together the tangible and the intangible. The thoughts and sense-experiences that slip in and out of our grasp can become material in some way through the art object, whether that be through the action of making the material object, or the way that the artwork is able to ignite our memory banks of images.

Gaston Bachelard in the Poetics of Space writes: “ At the level of the poetic image, the duality of subject and object is iridescent, shimmerIng, unceasingly active in its inversions. … The image, in its simplicity, has no need of scholarship. It is the property of a naïve consciousness; in its expression, it is youthful language. The poet, in the novelty of his images, is always the origin of language. To specify exactly what a phenomenology of the image can be, to specify that the image comes before thought, we should have to say that poetry, rather than being a phenomenology of the mind, is a phenomenology of the soul.”

Where am I going with this train of thought?

My painting is usually about landscape, but more specifically, it is about ‘place’ and its relation to memory and history. I am still catching up with the period of time - between 1997 and 2019 when I was not painting (though drawing sporadically) so was not reading a huge amount in relation to contemporary art practice.

I suppose our lived experience, memory and reach into the often unmediated and unresearched documents of the past, meld together over time an overwhelming amount of visual imagery, experiences, music, literature and poetry, alongside the phenomena of the natural world, that also enriches painting practice. These tap in to the visual, haptic and somatic.

Above: My nieces’ childhood drawings of my Mum looking flamboyant, and Little Red Riding hood? (note the question mark); Children’s book illustration hand coloured by Cleone Roberts in 1940s; enchanted sprite book illustration.

It is possible in a painting practice that makes use of the archive, to go beyond the dualisms of binary thinking that generates objectivistic, individualistic, and reductionistic characteristics. In the sort of critical thinking that has prevailed historically, skills such as conceptualising, applying, analysing, synthesising, and evaluating are used. As critical thinking separates subjects and objects, it ultimately promotes the values of independent individual beings and may exclude the collective and the interconnectedness of the world in which we live.

By looking at contextual sources within archives and a multiplicity of sources: - ephemeral material in charity shops and second-hand bookshops, geological or botanical drawings, family photographs, dusty tourist promotional material from past decades, industry documents and illustrations and engravings - material that is deemed less important or irrelevant due to the framework of culture that had previously excluded it, this can provide a more integrated way of seeing the past that takes account of those who have had control over the making of history, and those excluded.