How archival imagery and painting can work together.

Summer is my favourite time of year, so I find July and August good times to reflect - both on life, and on art practice. I suppose, like many of us, that I am still trying to fathom out the direction my work is travelling in.

Archive material is something that I have used only recently to develop paintings. This was in relation to the local group exhibition “Exile and Return” which was put together in order to commemorate the 80th Anniversary in 2025 of the liberation of the Channel Islands from Nazi occupation during WWII.

It has made me reflect on how we collect and curate our own personal archives throughout life - photos of friends and family, festival tickets, travel passes, stones collected from memorable places. They carry traces of the past into the present, to memorialise, re-imagine and make sense of our pathway through life.

But what is archive? What is its purpose? How does it relate to fine art practice? What is included (and excluded)? Who defines it and who does it overlook, hide or obscure?

The National Archives describe archives as “collections of information – known as records. These come in many forms such as: letters, reports, minutes, registers, maps, photographs and films, digital files and sound recordings.

Looking back, it seems that from around 2005, it became more common for contemporary art and academic discourse to focus on the archive. I guess this is possibly linked to technological change with increased use of the internet, and no doubt, the digitalisation of archive material. Work from this period seems to be connected with social practices such as commemoration, memorialising and observances of rituals and traditions.

Archives both work as places to store records and as catalysts for memory. They are often drawn on to commemorate important moments in history. Artists, haunted by past events, or trying to make sense of current political or ethically charged events, often engage with archives as sources of material; they may use them for research purposes; or even to consider the concept of archival memory in its own right.

In his book “an Archive”, Edmund de Waal reflects on this further:

“Archives are purposeful and they are random. They record the personal and the institutional, plural and singular histories. They are passed on, inherited, stolen, plundered, and lost. They are destroyed by accident and by design, They record rewritings, rethinking, retellings. They hold stories so they don’t disappear. They preserve information in the hope of a future. Archives cross all of the senses. They are tacit, digital , somatic, auditory.

These are the archives as places of memory.”

The archive can be used to consider the relationship between time, history and memory, and the ways in which we understand the passing of time in relation to the archive itself.

Here’s a rather random set of images that maybe aren’t so random.

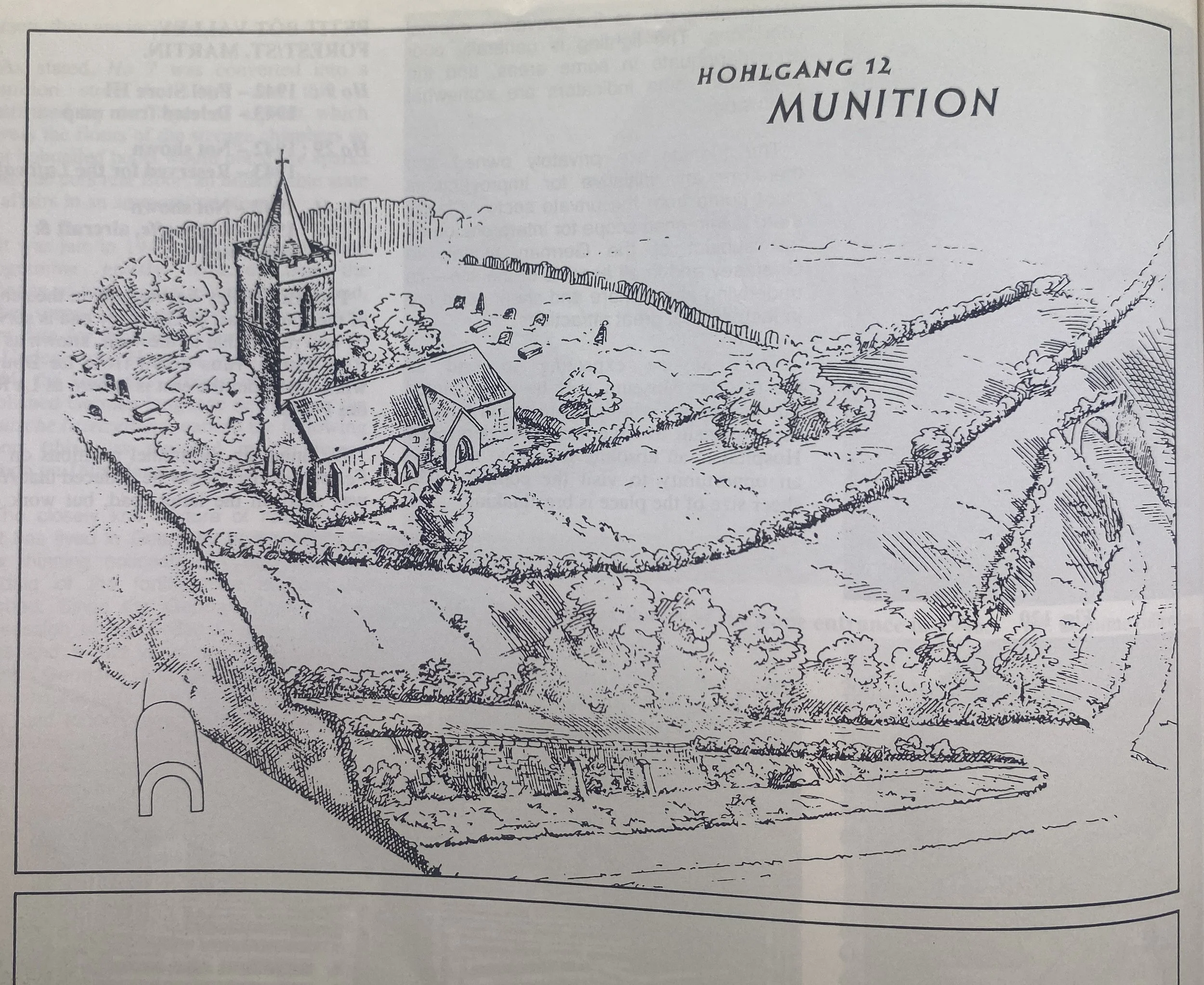

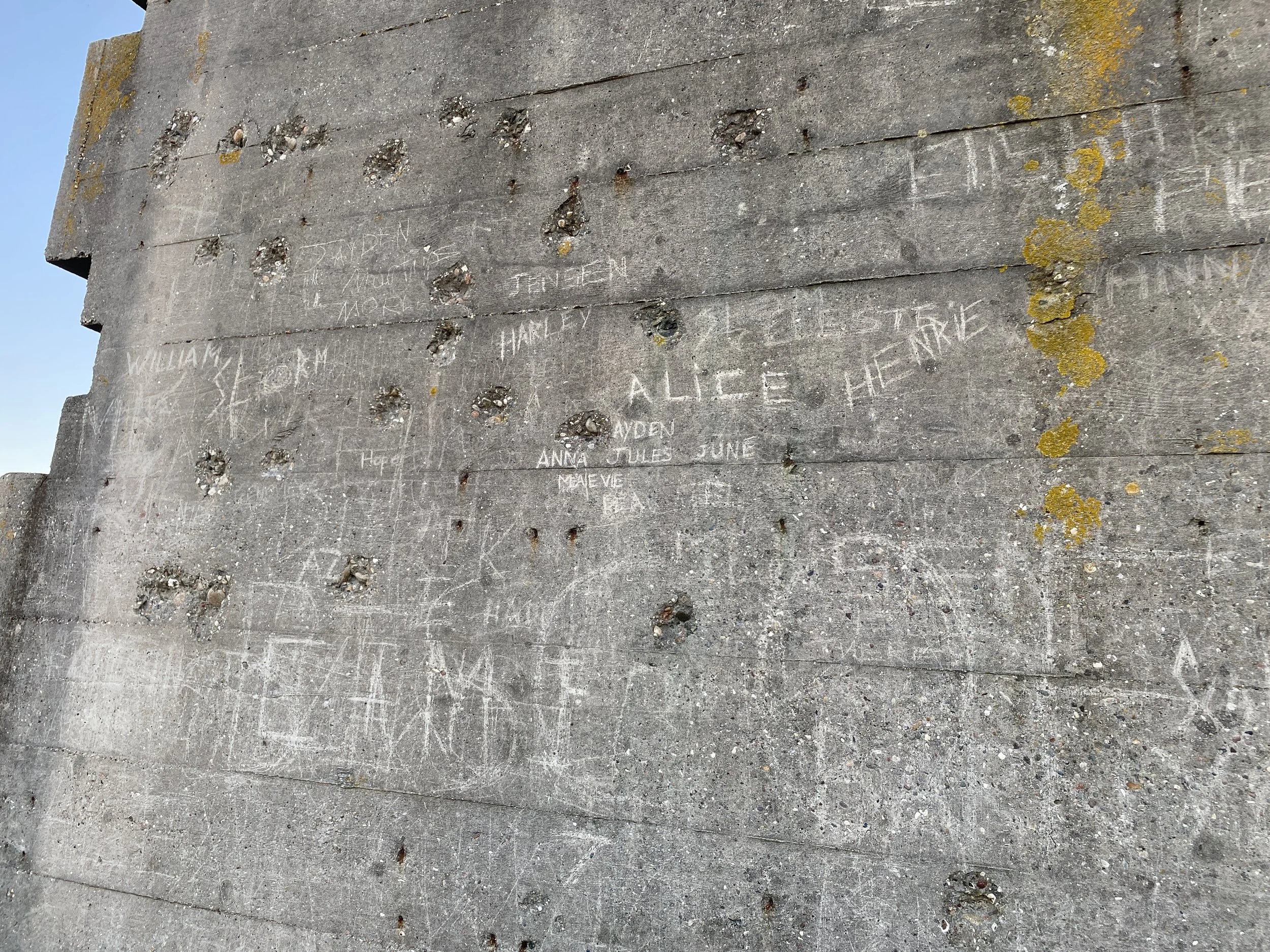

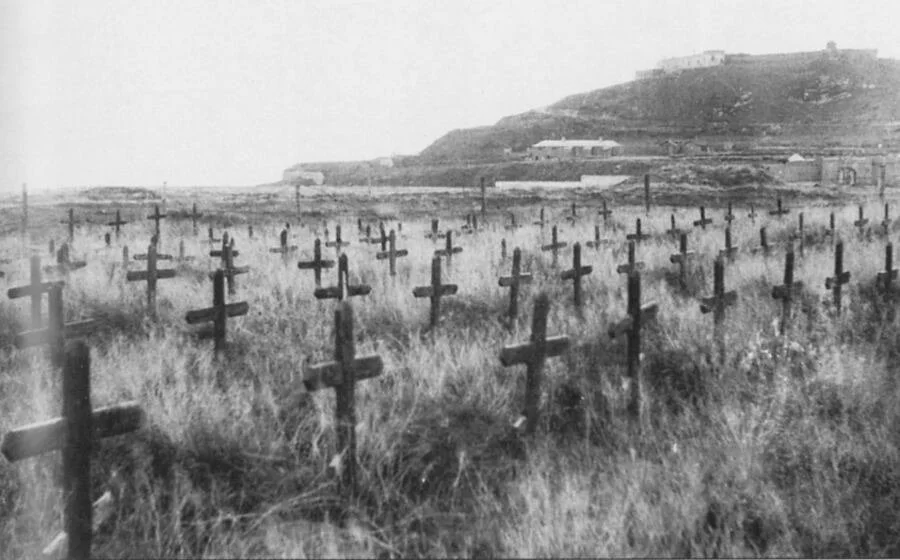

Diagramme of the German tunnels under St Saviour’s Church from WWII; My maternal Great-Grandmother’s Identity Card from WWII; Graffitti on the German Stone Crusher on L’Ancresse Common, used to crush stone for the cement used in fortifications; My Dad swinging over a German bunker in my Grandparents back garden; Sketch of the Vale Castle Guernsey, by John Mallord William Turner (1832); Burning of the huts that housed the Organisation Todt workers during WWII after the island had been liberated; Elliston’s Butchers - my Great-Grandfather, Grandfather and Uncle’s stall inside the Guernsey Market, 1970s; postcard of the Isle of Sark boat; my friend Ollie’s Grandmother - Guernsey’s last washerwoman, My Grandmother, Mother and Uncle; La Gran’mère du Chimquière, a megalithic monument outside the entrance to St Martin’s Church, thought to have been carved at two separate times - at around 2500 BC and then again during the Gallo-Roman period around 100 BC – 100 AD; A photograph taken by my grandfather in the 1950s of houses being built at Jerbourg, showing how much open land there was compared to today; Summer - the cat supervising baking; My late friend Stephen Palmer in his many guises; flag iris in St Peter’s Valley, Guernsey; orchid fields at Rocquaine Bay.

In making art, it’s hard not to reflect on the inescapable brevity of our time in the world and our relationship to what has been before and what comes after. The sheer timespan of visual representation from the cave paintings through to today’s art world sometimes feels overwhelming, if always a source of joy, awe and contemplation.

With the dire situation of climate emergency, and so much conflict, war, displacement and uncertainty around the globe, there is perhaps a need to explore if and why the nature and role of painting is still a relevant form of representation for the 21st century. It somehow feels important to do this, rather than just continuing blindly to make more imagery in a world that is saturated with the visual.

History and place is the ground for all representation. It is dialectical. We cannot escape the fact that we are all constructed in the specifics of a place and time; the beings that we are, are formed through our histories, personal and collective, yet we are simultaneously the makers of our own history. We are all situated differently due to the structures of our social environment, yet we are also actors in the world, who need to dream and to see possibilities for change and for the future.

Painting and drawing feel like apposite ways of considering the limitless possibilities in life and the elements of chance and action that form it. The fleeting contingency of mark-making with charcoal, pigment and oil embraces experiment, destruction, loss and transformation of the creative object. They are connected to us bodily, as a fleeting moment in time, both through the markmaking and the organic nature of their makeup. Markmaking is both intuitive and reflective, involving both thought and action.

Above: Moulin Huet Bay painted by Renoir; A phograph of a local jellyfish - once not seen often locally, human actions are making life easier for them. As vertebrates are disappearing (mainly due to overfishing), invertebrates have greater opportunities to occupy their niches. Huge jellyfish blooms may also be due to rising ocean temperatures and decreasing oxygen levels due to global warming; Wild allium on the headland at Port Grat; the German stonecrusher at l’Ancresse Common; Summer sea mist at Rocquaine Bay; Waving or drowning? Underwater swimming.

The constant laying down of paint or charcoal, erasing, rubbing back of paint and remaking, seem to be the material counterparts of personal memory and of the collective memory that we label ‘culture’. One could also draw analogies with the political recollection and construction that we name as history.

Memory and history make us who we are; the depiction of our worldly condition. Making visual art is confounding but it also understands that within life there are so many unknowns amongst the knowns; so much contingency. Art is not bounded by empirical, verifiable views of the human experience within the world. Artists get that. They understand that the measurable is insufficient to capture human experience. Art is therefore so valuable in exploring and expanding on the understanding of ‘what is’ and how we might understand ‘what exists’ or ‘what could be’.

The Enlightenment struggled for reason over beliefs and passions, science over superstition. The victory of reason was also misapplied to compound the issues of the pre-modern world. One outcome was colonialism which exploited and subjugated people across the world. As Walter Benjamin wrote: “There is no document of civilisation that is not at the same time a document of barbarism.”

This statement is a rebuke to the philosophy of historicism - the idea that history is made transparent through the gathering of evidence (dates, events, documents). That history is chronologically linear and narratives that mirror the past as it happened are faithful and correct, and constantly move in a progressive trajectory. This view of the world diminishes the role of human agency. It accepts the official records of history, without acknowledging the fact that those in power are the ones who shape the history books.

Looking back at history and using archive material within the creation of art is generative. It allows us to mesh together the tangible and the intangible. The thoughts and sense-experiences that slip in and out of our grasp can become material in some way through the art object, whether that be through the action of making the material object, or the way that the artwork is able to ignite our memory banks of images.

Gaston Bachelard in the Poetics of Space writes: “ At the level of the poetic image, the duality of subject and object is iridescent, shimmerIng, unceasingly active in its inversions. … The image, in its simplicity, has no need of scholarship. It is the property of a naïve consciousness; in its expression, it is youthful language. The poet, in the novelty of his images, is always the origin of language. To specify exactly what a phenomenology of the image can be, to specify that the image comes before thought, we should have to say that poetry, rather than being a phenomenology of the mind, is a phenomenology of the soul.”

Where am I going with this train of thought?

My painting is usually about landscape, but more specifically, it is about ‘place’ and its relation to memory and history. I am still catching up with the period of time - between 1997 and 2019 when I was not painting (though drawing sporadically) so was not reading a huge amount in relation to contemporary art practice.

I suppose our lived experience, memory and reach into the often unmediated and unresearched documents of the past, meld together over time an overwhelming amount of visual imagery, experiences, music, literature and poetry, alongside the phenomena of the natural world, that also enriches painting practice. These tap in to the visual, haptic and somatic.

Above: My nieces’ childhood drawings of my Mum looking flamboyant, and Little Red Riding hood? (note the question mark); Children’s book illustration hand coloured by Cleone Roberts in 1940s; enchanted sprite book illustration.

It is possible in a painting practice that makes use of the archive, to go beyond the dualisms of binary thinking that generates objectivistic, individualistic, and reductionistic characteristics. In the sort of critical thinking that has prevailed historically, skills such as conceptualising, applying, analysing, synthesising, and evaluating are used. As critical thinking separates subjects and objects, it ultimately promotes the values of independent individual beings and may exclude the collective and the interconnectedness of the world in which we live.

By looking at contextual sources within archives and a multiplicity of sources: - ephemeral material in charity shops and second-hand bookshops, geological or botanical drawings, family photographs, dusty tourist promotional material from past decades, industry documents and illustrations and engravings - material that is deemed less important or irrelevant due to the framework of culture that had previously excluded it, this can provide a more integrated way of seeing the past that takes account of those who have had control over the making of history, and those excluded.

Above: My father in Crail, Scotland; my aunt Joan and her first husband before they were married, model yacht pond, Guernsey, plus a great aunt in the best sunglasses; Grandparents’ 1950s kitchen; Vazon Bay 1950s; My great-aunts Rae and Bessie with cucumbers and grapes ;-) ; Myra, my grandmother; a garden rake; St Peter Port Harbour 1950s.

My paternal grandfather’s photographs are an archive of his married life which span from the date his twins were born in 1938, when he bought a Leica camera in Scotland, through to the 1960s and early 70s in Guernsey when his grandchildren were born. I have inherited the negatives and hope to bring them to life for new audiences in the 21st century along with photographic material from my mother’s side of the family.

Although this could seem like a nostalgic or romantic dive into a better and simpler way of life, I do not wish to return the island or the world to the past. I am moved by many of the images, but also find it fascinating that the two sides of my family straddle both class and geography. Like most who inhabit islands, we are local, but partly outsiders to those whose entire family have been islanders for generations. I think that this sense of belonging but not belonging, engenders both curiosity about life and other world views, plus empathy for those who feel or appear ‘other’, as most of us are at some points in life and those who are transient, marginalised or displaced.

To me, looking backwards in time through the use of personal and institutional archive material is meaningful as it offers the opportunity to ask broad philosophical questions about meaning and knowledge and draw out narratives and parallels from the past. It provides gaps and spaces that allow for chance and contingency, like life, which can be used to re-interpret and tie together multiple layers - the everyday, the astonishing, the beautiful and the horrifying, allowing the viewer to place themselves and fathom their way into the artwork.

Above: Drawings made in Guernsey bunker by homesick German soldiers of forest trees native to Germany, presumably to make the place more homely and comforting; Statue of Victor Hugo in Candie Garden - Hugo was exiled in Guernsey and while here, helped many of the poor in the island; A mine being exploded on a Guernsey beach after WWII; the Russian Cemetary at Longis, Alderney - the principal burial ground for foreign workers for which records were kept by the Organisation Todt (OT).

Feminist scholar Kate Eichhorn, in a response to the political and economic impacts of neoliberalism, considers that “a turn toward the archive is not a turn toward the past but rather an essential way of understanding and imagining other ways to live in the present...an attempt to regain agency in an era when the ability to collectively imagine and enact other ways of being in the world has become deeply eroded.” (Eichhorn, K. (2013). The archival turn in feminism: outrage in order. Philadelphia: Temple University Press).

Making, and indeed, relational thinking that focuses on the interconnections and interrelations that cross disciplines and high and low culture, and multiple sources of reference material allows us to pull out of this maelstrom of sense experience some form of visual representation of the here and now that takes account of the historical. Maybe, through the poetry of the painted or drawn image, and photography, they may provide echoes of possibility for the future that are transformational both in terms of making and art practice, and in terms of ways of collectively being in the world.