Mysterious and Dark Guernsey Landscapes

My last post here focused on why Aaron Yeandle and I are showing work together next year and the similarities and differences in our work. In this article, I really wanted to consider Aaron’s landscape photography in its own right. We spoke a bit about his journey into photography, his influences, and why he enjoys making landscape work as a counterpoint to his portraiture projects before Christmas. Since then, I have been looking at individual photographs from his night photographs in isolation, reflecting on why the particularity of each image resonated for me. I appreciate that this is a very subjective, and perhaps self-indulgent way of appraising the work of an artist and friend, but as someone who is not well versed in the history of landscape photography, it felt like the only way I knew how.

Graduating with a BA in photography in 2001, Aaron followed this a few years later with an MA in fine art. He had known from early on in his art education that he had no interest in becoming a commercial photographer, wanting instead to make work that communicated his own personal vision and inner emotional landscape. Initially when he went to art college, he had wanted to become a painter, but had got wrapped up in photography early on and found he had a real flair for and enjoyment of the medium. His strongest influences though have always been painters rather than photographers and he enjoys viewing exhibitions of painting, understanding intuitively what makes a successful painting.

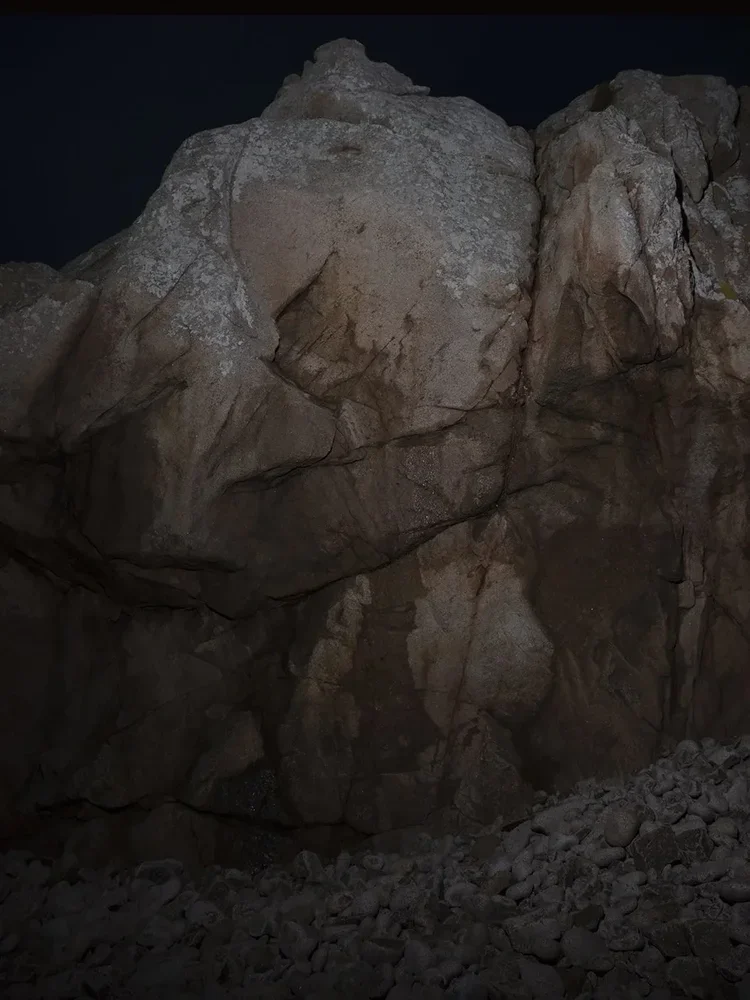

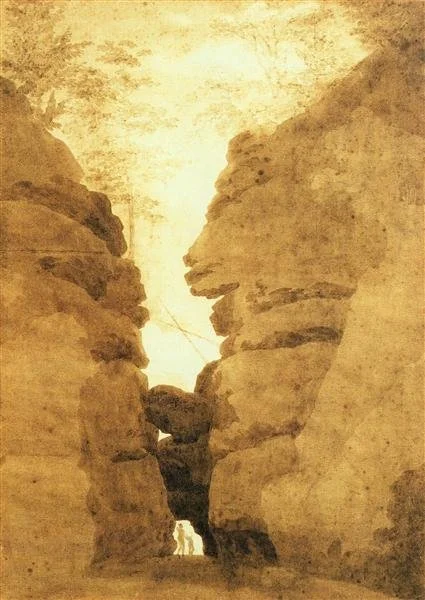

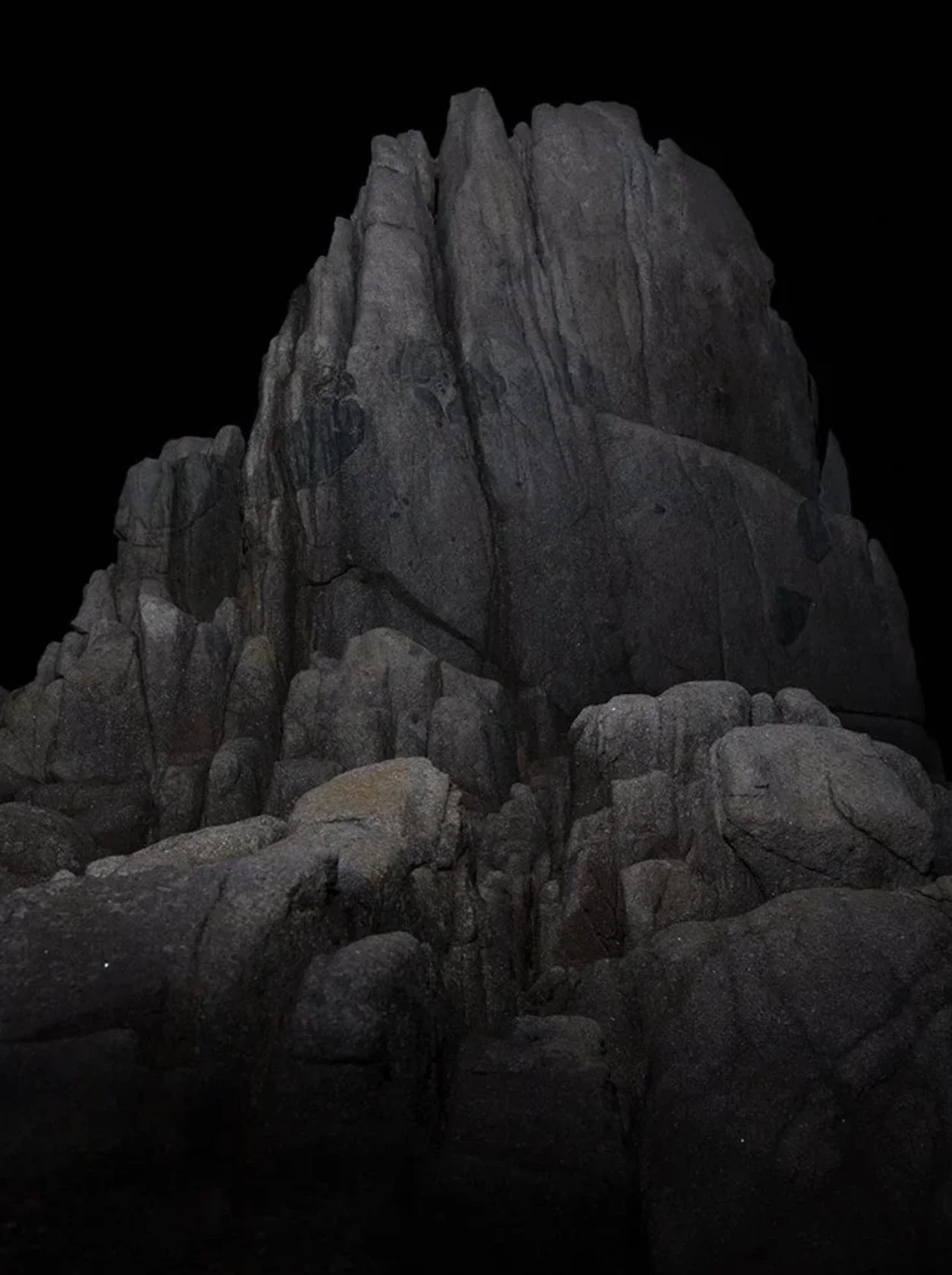

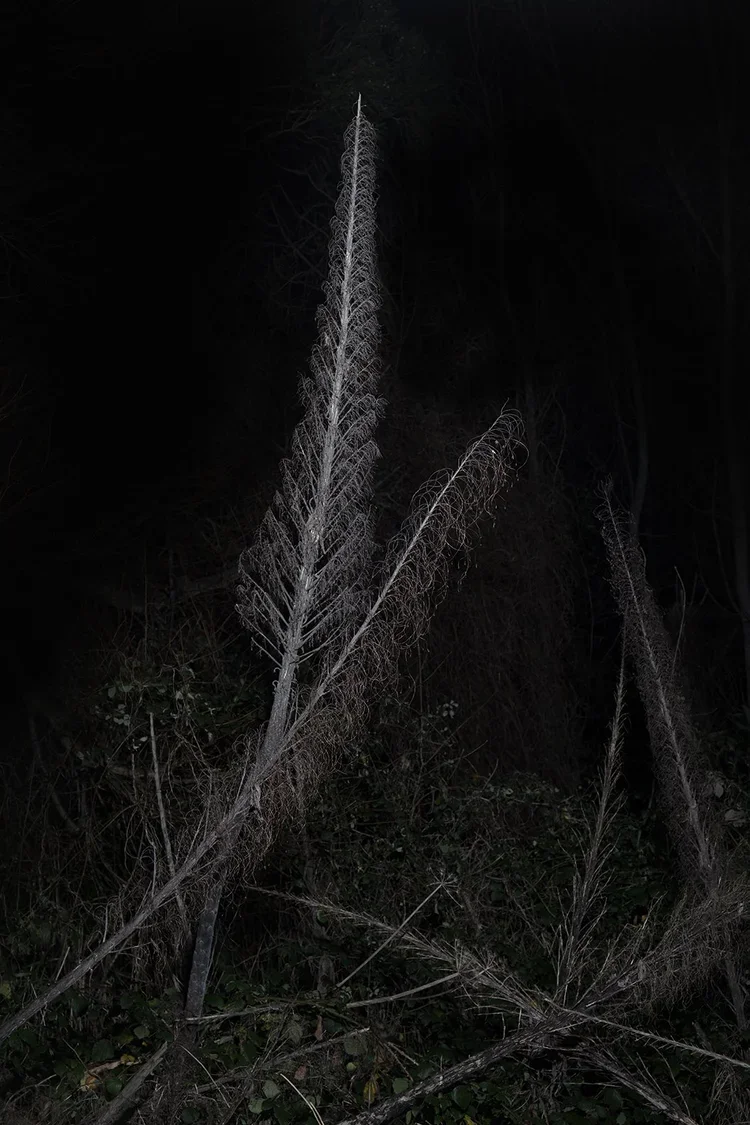

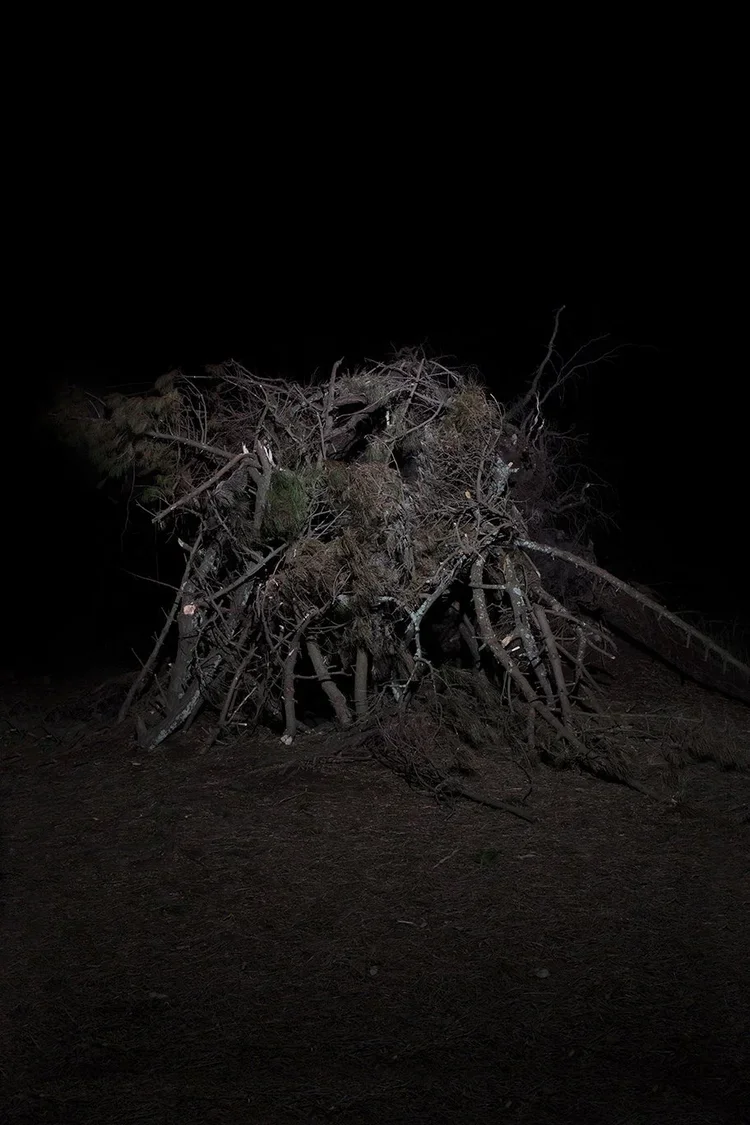

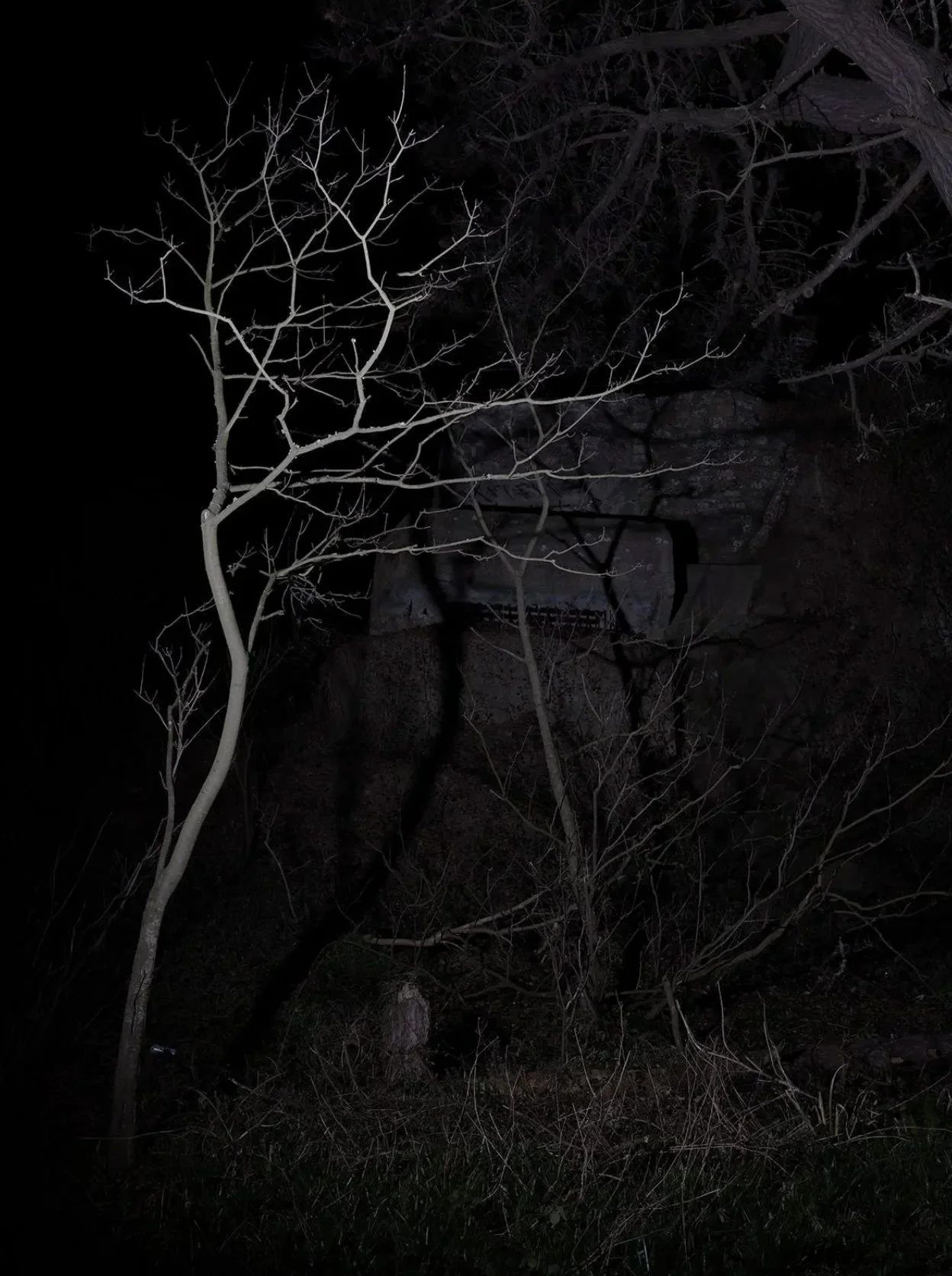

His favourite painter is Casper David Friedrich, the German romantic painter of the late 18th century and early 19th century. The influence of Friedrich is really palpable in many of Aaron’s photographs, particularly the rocky crevasses and eerie ruins. It is also there in the way he plays with scale and perspective to make the viewer feel a sense of awe, but also an element of confoundment, in not being able to quite work out how near or how large his subject is. Looming out of the darkness it is sometimes difficult to read whether it is a microcosm within the forest floor or redwood pines looming hundreds of feet above in relation to the human form.

Above - Aaron’s recent photographs interspersed with paintings by Caspar David Friedrich.

Talking last week over lunch, Aaron told me that landscape work has always been a thread running alongside his better known portraiture work. He said:

“It is a natural thing for photography and landscapes and painting to come together. And especially in Guernsey. A lot of people here consider landscapes in Guernsey to be beautiful. And for them, that is what photography captures. Well, see, I don't do that. It's a whole different way of looking at our environment.” He views the camera as a tool to capture and create his art practice - his kit is something important to master, but not to obsess about or fetishise as some photographers seem to do. He believes that if other photographers were to pick up his camera, and photograph the same places, they would produce very different sets of images to the ones he makes.

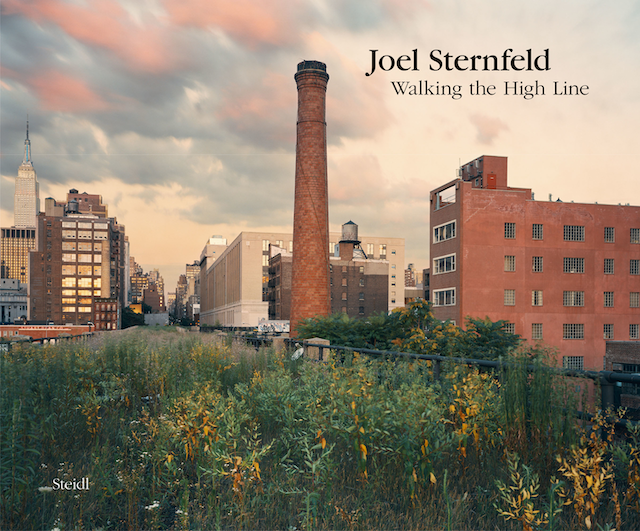

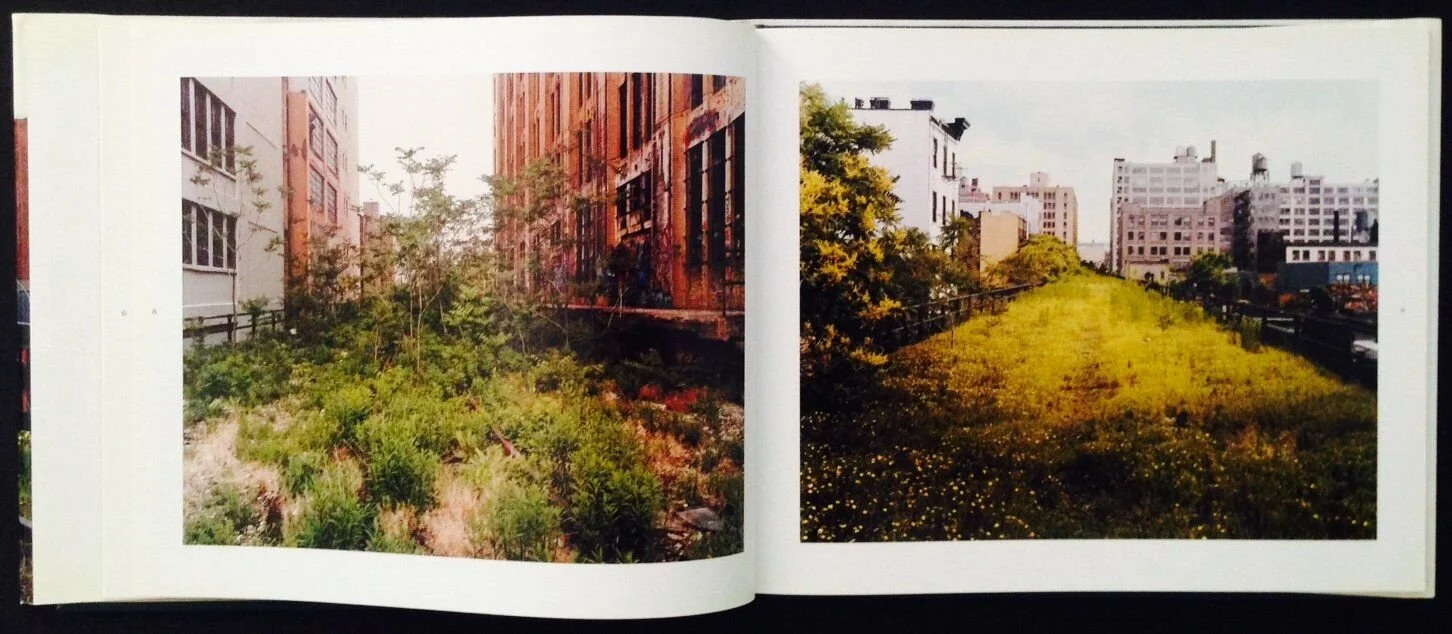

American photographer Joel Sternfeld’s project “Walking the High Line”, is a body of work that resonated with Aaron early on. This shows made a derelict railway line and buildings in New York, photographed in the late 1970s. It is a forgotten commercial line of a mile or so in length. Aaron said “The rural had started to take back all the urban land, so they're really beautiful. It's kind of bleakish, but it's how nature's been reclaiming from man.”

Above - images from Joel Sternfeld’s ‘Walking the High Line’.

The Photographer, Gem Southam’s “The Red River” made in Cornwall in the 1980s, is another of Aaron’s influences. Southam captures the interconnections of industry and a manufactured landscape with the natural world. The Red River was considered to be a real paradigm shift at the time, when working in colour was uncommon, and his compositions and close up angles were very different to the norm. These images though were interspersed with traditional landscape imagery which were influenced by English Romanticism. His work contained the straggling ruins of Cornwall’s tin mining past as they slowly merged with the plant life and waterways.

Above - some photographs from Gem Southam’s ‘The Red River’.

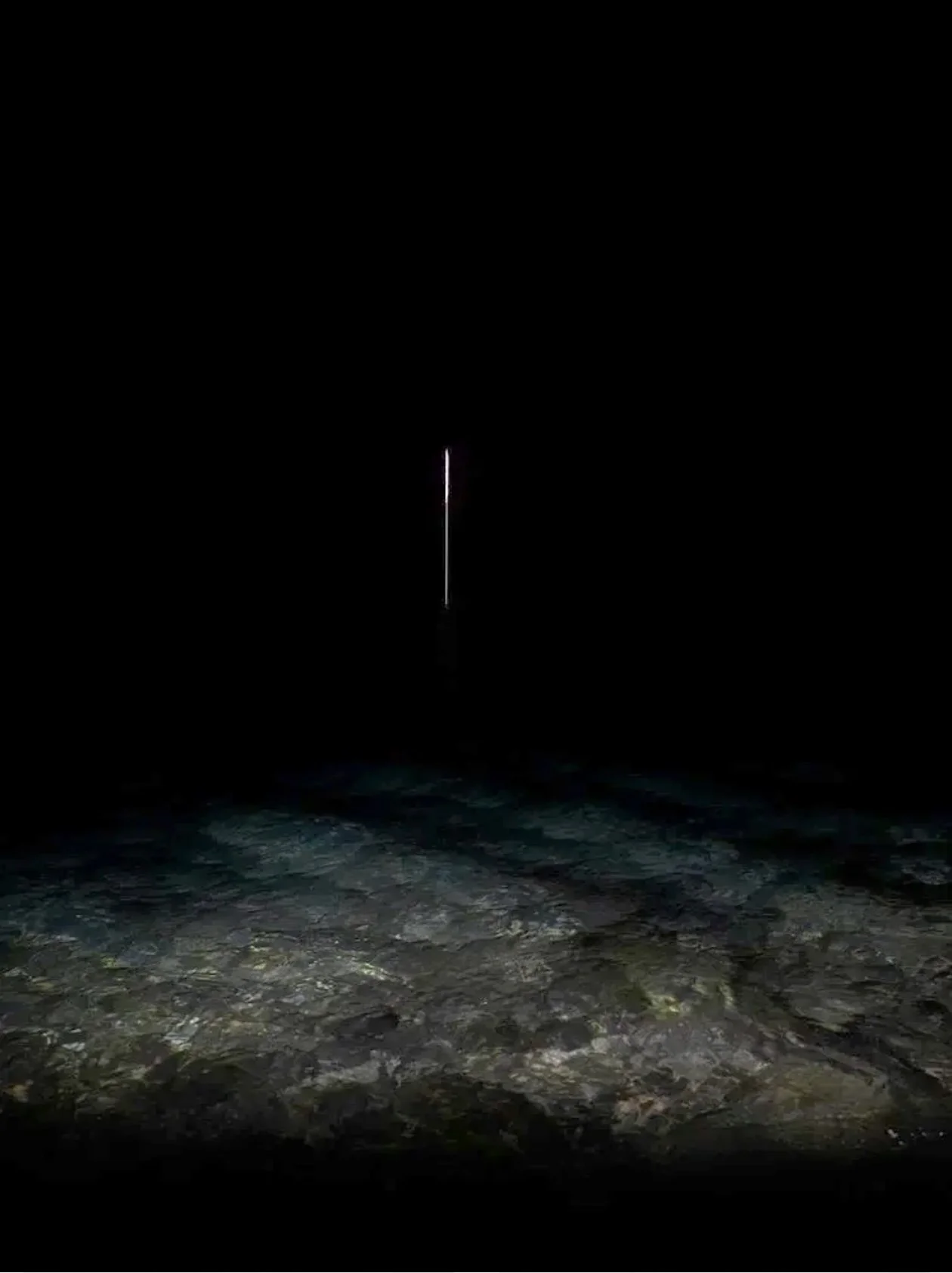

“Southam saw the landscape as a confluence of its inhabitants and the valley’s primordial formation and ancient mythologies. The Carboniferous granite, Bronze Age adits, and medieval tales of travellers lost on a winter’s night, stumbling upon a solitary illuminated window exist in harmony within these photographs. The artist explores the concept of history itself in this series, which he sees concentrated within this river and its fern laden banks.

Southam drew heavily from the Book of Genesis for this project: a tempest over a dark sea, punctuated with white capped waves references God’s creation of light and darkness out of a formless void. Primeval elements of the landscape, foliage and the rushing of the river’s red water, reference the second day of creation. Bucolic idylls juxtapose representations of the despoliation of the Earth and its subsequent regeneration. Southam’s relationship to the English landscape was profoundly influenced by poetry, in particular works by Beowulf, John Milton, and John Bunyan.

Wandering throughout the valley and beside the stream, Southam recalled Milton’s depictions of Paradise, lost and then regained; images like Valley of the Barking Dogs, Brea Adit draw from the apocalyptic imagery of Paradise Lost, while others are akin to the beatitude of Paradise Regained. The photographer saw an allegory in his journey along the Red River that went beyond local history, something universal wrought within all of the valley’s shattered remains and ‘poisonous tang’, as he calls it, its beauties and redemptions .”

anthropomorphism, folkloric, colour as warning, poisonous tang - danger

colour - minimal, common misconception that they are B&W works

vanished events - history concealed and revealed

stillness - slowing down in an age of digital overload - detail unravelling, stillness and slowing, reflecting

scale - bachelard