Tying together the underpinnings of a joint exhibition

In the last few months, I have been making paintings for a joint exhibition with the documentary photographer Aaron Yeandle. The focus of the exhibition is landscape - the Guernsey landscape specifically. In trying to think how our work would fit together, it’s made me reflect on the reasons why we feel an affinity for each other’s work; on the work’s similarities and differences; and how our approach to landscape differs from many other local artists.

Landscape has always been a contested term, meaning different things to different people. In the west, it was only officially considered an independent genre in the 16th century, and one that was seen as inferior to history painting, portraiture and still life. In the late 18th century it came to prominence, during the rise of Romanticism. Many other approaches followed in the 20th century. Today, landscape is a vibrant field, with artists exploring diverse themes and incorporating media such as photography and film as well as landscape art, installation and site-specific work.

Compared to traditional art, contemporary landscape work is far less likely to be concerned with the picturesque. It can be used as a way of thinking about cultural, social and economic development, environmental degradation, urbanisation, displacement, ‘nationhood’, colonisation and warfare. Landscape is often deeply rooted in human experience, and it covers the urban as well as the rural, the decaying and derelict as well as the beautiful and sublime.

The term does not only apply to representation of the real. Landscape can be an imagined place; it can also be a psychological space conjured up via half-remembered dreams or reverie. It is often a potent carrier of memory and identity, as well as a conveyor of emotions, capturing and embodying how the painter or photographer feels in the world. This can be done through the use of evocation and metaphor, the symbolic, allegorical and the poetic. For many artists, landscape is a means of exploring the human condition and our relationship with the world and with other life forms.

At this point when the planet is so dominated by humans that its ecological balance has ended, images of landscape can sometimes make us view the world differently. We are living in post-natural times, in a world in which the use of fossil fuels has altered the earth’s atmosphere, our waterways and oceans are polluted by fertilisers, industrial waste and plastics, and intensive farming has depleted the health of the soil. It feels like a time when our ecology’s existence is on a knife-edge. Images of our habitus provide us with the means to locate ourselves as subjects in relation to ‘place’. This is never more telling than at a time when areas the world frequently hit by devastating floods and wildfires and remedial actions to address climate extinction are too little and too late.

…….

A couple of years ago, Aaron and I had a conversation about how our work often had a similar quality that was apparent to us and others, but difficult to pinpoint in words. We said it would be interesting to curate a show of our work if the right opportunity arose. I thought that exhibiting our work together would make our painting and photographs become even more ‘of themselves’ through the contrast between the media and the dialogue between the work. Last summer that was made possible when we asked Adam Stephens of the Gate House Gallery if he had any free gaps in his diary for 2026.

In trying to unpick why Aaron’s photographs and my paintings often seem to evoke a similar atmosphere, we have talked frequently, if haltingly, about why we make the sort of work we do, and how our work seems to connect.

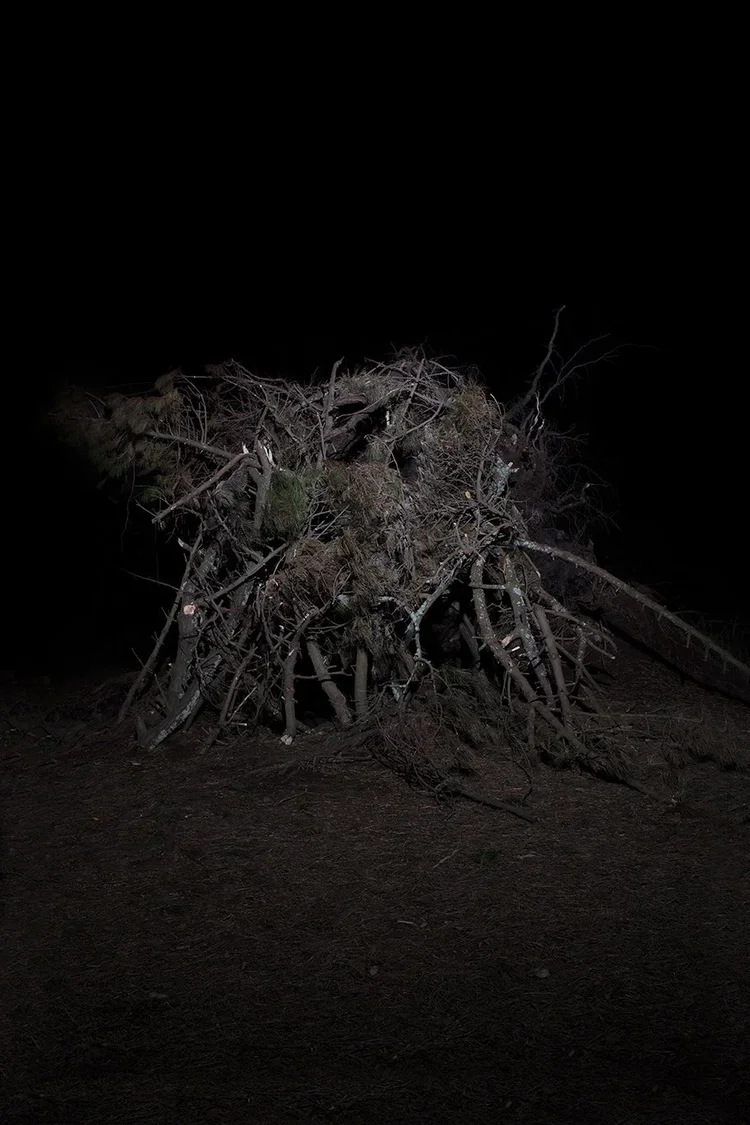

Like Aaron, I do not focus on the landscape in relation to its picturesqueness. The typical views of west coast sunsets or the steep cliffs and turquoise bays of the south coast are, without doubt, wonderful, but they do not interest me as subject matter for paintings. We both seem to be drawn to the spaces that people walk past unseeingly; to the spots that many others view as eyesores. The taken-for-granted hinterlands where thistles spread rampantly, gossamered with spiders nests and dew.

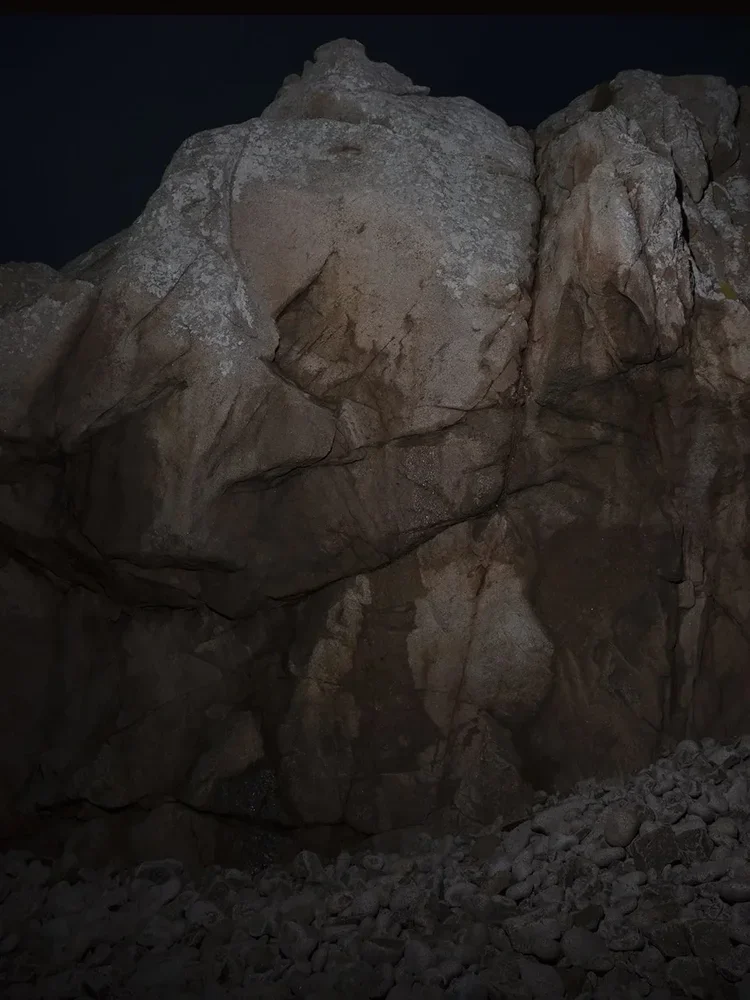

Other areas of the island draw us as they hint at the sublime, but perhaps in a less pronounced way than the archetypal views of mountain crevasses or the ocean’s stormy abyss that the Romantic tradition is known for. The places that draw us are sites that appear to hold a darkness. They somehow underscore and intensify our sense of human fleetingness in comparison with the deep time of the rock formations and landmasses that they conceal. The knowledge that these sites existed several millennia before humanity provides a powerful lens for understanding human impact in the age of the Anthropocene.

It’s impossible to write about a two-person show featuring photography and painting without considering the relationship of these two media and their differences. Painting is a shifting elusive entity that flickers between what it is depicting and its ‘objectness’, i.e. its material embodiment of oil on canvas or watercolour on paper. Painting are one-off objects that are produced by the physicality and existence of their maker - through the impact of our senses and our memories, via the context of our own history. Their making involves layering and time. Once autonomous from their maker, or even before this, they flicker into life through being observed by a viewer.

Paintings involve mark and gesture. Making them is an embodied act and their meaning can, in part, be intuited through the action of painting or drawing which remains in the structure of their being, embedded in their surface and texture. The objects produced are records of the movements, emotions and spirit of their maker that have existed in time.

There is a duality between the ‘objectness’ of the painting and its way of creating space, pattern or colour field as virtual space. Painting is illusory, and often makes use of artifice through the use of perspective and representation, yet materially, it is made from the earth that we occupy and many of the same components as our bodies.

While photography is also made through the hand, the eye, and an evocation of the senses, it is captured through mechanical, chemical and digital means and can be used to make multiple versions of the same work. While the first examples of photography were set up to record reality, its traditional documentary and scientific function has moved in multiple directions since the early 1800s, one of which is contemporary fine art photography.

Photography is an accepted medium within contemporary fine art practice. It is able to adopt elements of painting, cinematography and performance and it plays with form, lighting, composition and narrative in similar ways to painting. Photographers regularly combine documentary and conceptual methods to explore personal yet universal visual themes, as can painters should they wish to.

Like painting, photography has an ability to capture elements of the landscape that reach beyond the powers of the eye. Photographs can both simultaneously be a means of expression and of investigation. A photograph is a frozen moment where time feels like it is suspended, but, like painting, it has the ability to make the familiar seem unfamiliar through the singular vision of its maker. This can be used to reimagine and represent the landscape in ways that displace the privileged human viewpoint. To the viewer, this can unsettle our centrality as subjects making us look again at what is in front of us, in ways that range from the startling and shocking to the gentle and slowing down.

Since the outset of photography, painters have made use of it, both as reference material for their work, and to illuminate their own practice by seeing the world differently post-photograph. Images from the archive are often used by painters (myself included) to tap into the pathways of memory and imagination. They can be used to release new meanings from the past that seem to have bearing on the present.

…….

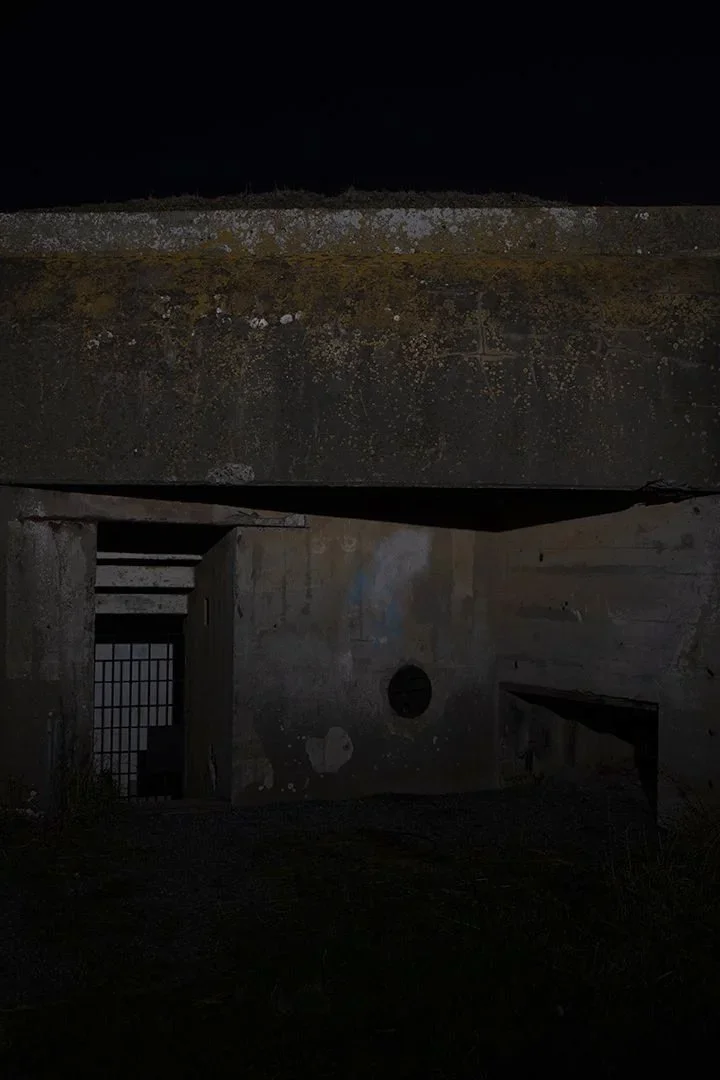

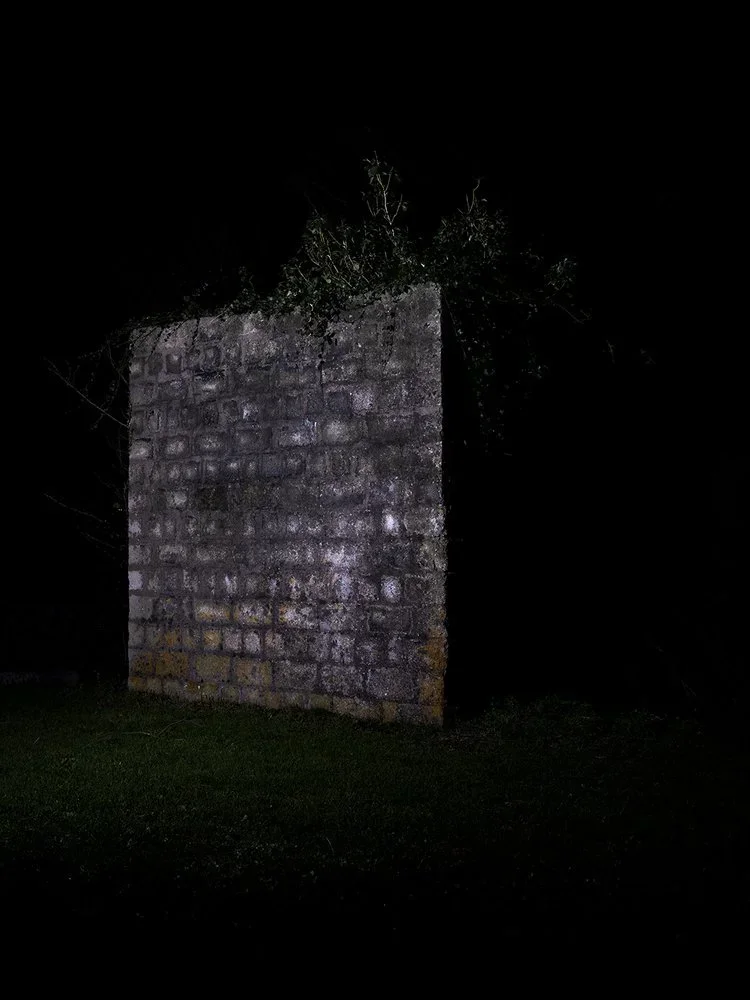

So often on a small island we travel the same routes, take in the same air and pass the same buildings week in and week out. In doing so, it is easy to fail to notice those commonplace constructions and artefacts that have become a taken for granted part of our terrain. The thousands of bunkers scattered across the landscape, their graffitied surfaces memorialising lost love; the corrugated walls of an abandoned flower packing shed empty and forlorn; or the rusting bulk of an industrial steamer, buried deep amongst bracken and brambles. Our painting and photography draws on these forgotten and abandoned sites that hold the weight and layers of our social history.

Sites of myth, storytelling and the sublime – the fairy ring and the megalithic burial tombs; the enormous coral granite headland at Albecq – still prickle the hairs on my neck, especially in a certain low winter light. Aaron who has lived here about 15 years said he feels an inexplicable darkness in Guernsey that lifts from him when he travels off island. Perhaps this is all I have really ever known, but I feel at peace with Guernsey’s shadowed vales and shrouded landmasses.

Aaron and I are both interested in the changes to the land and how history and industry shape it. This is a huge subject in its own right, which deserves more time and thought than is available now. Inevitably though, our discussion on the nature and changing face of the Island often moves on to how built up it has become. This is an enormous challenge to biodiversity, but it also impacts on the everyday pleasure of wandering the lanes and valleys – memories of which are signifiers of my free-range, nature-obsessed childhood.

The Island has become more affluent since the arrival of the offshore finance industry (or should I say, the affluent have become more affluent and the wealth gap has grown). This wealth is once again re-shaping the landscape. Huge mansions appear to spring up every few months, replacing modest bungalows and 1930’s family homes. Heading inland from the high western cliffs a few weeks ago, another new vast steel-framed construction appeared in my eye line - a looming skeletal brachiosaurus overshadowing the modest granite cottages of the hillside below. Change is inevitable and often positive, but it remains seen whether the growing wealth of the islands richest decile will improve island life as a whole, and not just be to the detriment of the ecology and the less well off.

While making a political statement is never the focus of my work or Aaron’s, and is not an objective of the exhibition, the political and social are embedded in our work, as they are in every part of life. What do we wish to achieve with this exhibition? I guess this would be for its viewers to spend some time with our work, think about the natural environment around them, and perhaps happen upon some of those everyday sites just through wandering aimlessly without map and viewing the island and its sister isles and islets with fresh eyes.

This post started out as a piece of writing about Aaron’s work and influences. Having been drawn off on a tangent, a bit like my walking habits, this will follow in the coming weeks so it can be given the full attention it deserves.